Is the world broken?

Have you ever thought about the problem of evil and suffering? Have you ever asked, “Why is the world so cruel?”

My daughter came to me crying. “Why do Mom and Lyla have to be sick? If God exists and is good, why is there suffering?”

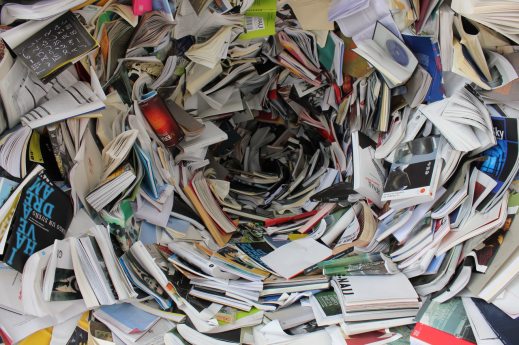

As I thought about how to answer, tears came to my eyes and an image came to my mind, a shattered platter. By looking at the shattered shards you could tell the platter used to be ornate and beautiful. Upon reflection, that seems like an accurate picture of the world. It certainly seems broken, but yet it has clear traces of beauty.

What happened? How did the platter get that way? If the platter is broken, it seems to make sense that it was previously whole. Otherwise, it would not be broken; it would just be. The shattering, the brokenness, is just the way the world is. There, then, was no previous better state, nor should we expect a future better state.

So either the brokenness of the world assumes a previous state of the world that was whole and good, or there is no wholeness, only shattered shards that were never part of a whole and never will be. Everything is either light with little pockets of darkness, or everything is darkness with little pockets of light.1

Are beauty, goodness, and love innate, or are they random meaningless sparks in a universe that is growing cold? A world without God may have a few pockets of light, but chaos should be expected.2 If God exists, however, and Christianity is true, then chaos is not the final state of the world.

We intuitively sense that the world is broken. We feel it in our bones metaphorically, and some of us feel it literally. How could the world be broken if it was not at some point whole? It seems, therefore, we can make a deduction from the broken state of the world to the original good design. Or else our hope and intuitive sense that something is wrong is wrong.

Whole

The Bible says God created the world whole. The original creation was very good (Genesis 1:31). The platter was ornate and beautiful, so to speak. No disease or need for dentures. No sin or suffering. No turmoil or tears. No fighting or fears. No death and no destruction.

Christians believe “the bedrock reality of our universe is peace, harmony, and love, not war, discord, and violence. When we seek peace, we are not whistling in the wind but calling our universe back to its most fundamental fabric.”3 Christians believe in evil, and they believe it’s a problem. The world was not supposed to be a place of suffering. Evil and suffering are not a hoax, but they don’t have a place in God’s good intentions. The world is broken.

Broken

The platter shattered. The world broke. Sin unleashed suffering, disease, destruction, and death. The brokenness of the world and the messed up nature of humans are teachings of Christianity that can be confirmed by turning on the news.

Christianity explains the origin of the problem of evil and suffering and makes it clear that it is a problem. That is, Christianity says suffering is not innate in the way the world was supposed to be. And Christianity traces the problem of suffering to a historical cause.

Christianity not only says there’s something wrong with the world, it says there is something wrong with humans, with you, and with me.4 It’s not easy to admit our faults, but to deny there is anything wrong with humanity is to say that this is as good as it gets.5 That, also, is not a happy conclusion. Better to face reality head-on than to stumble in a land of make-believe.

Naturalism, in contrast, does not seem to give a sufficient answer, other than suffering is just the way of the world. We’re essentially animals, so we’re going to be animalistic, and so suffering will result. We’re in a world of chaos and chance, so the world will be chaotic. There is no real problem of suffering, there’s an expectation of suffering. Or, there should be. And for naturalists, there is no category for evil.6 Evil gives off no kinetic energy. There is no entity to evil. Various people may have opinions, likes, and dislikes, but from a strictly naturalistic perspective, there is no evil.

Another problem is that “modernity cannot understand suffering very deeply because it does not believe in suffering’s ultimate source.”7 Modernity will then never find the true answer to suffering. If I fix a leaky sink in my house because I notice a puddle and mold, that may be helpful, but it will not fix the problem if the problem is a leak in the roof. If we don’t know the origin of a problem, there is no hope of fixing the problem. We will be left with external shallow bandages. As I say elsewhere, naturalism cannot truly identify evil as a problem because evil, for naturalism, does not exist. If evil is not seen as a real problem then it certainly can’t be solved.

As Peter Kreeft has said, “If there is no God, no infinite goodness, where did we get the idea of evil? Where did we get the standard of goodness by which we judge evil as evil?”8 Or here’s how C.S. Lewis said it: “My argument against God was that the universe seemed so cruel and unjust. But how had I got this idea of just and unjust? A man does not call a line crooked unless he has some idea of a straight line. What was I comparing the universe to when I called it unjust.”9

The Bible says sin and suffering are not original to the world; sin and suffering have a beginning in history, and they are not a feature of humanity or the world as originally created.10 That is good news. We do not have to be left in our broken state. We sense that not all is right in the world or in our own hearts and lives. The Bible agrees. Yet, that is not all; it says there is a solution.

The Broken Healer

While writing this, my daughter came into the room and said her bones hurt. That is part of her condition. She has CRMO, which stands for chronic recurrent multifocal osteomyelitis. Basically, her body attacks her own bones, inflammation causes liaisons and fractures her bones, which can lead to deformity. It could stop harming her body when she stops growing, or it could continue her whole life. She currently gets infusions at Nationwide Children’s Hospital in hopes of putting it in remission.

How does Jesus relate to her pain? As Jesus’ biographies relate, “Jesus on the night that He was betrayed took the bread and broke it and said, ‘This is my body which is broken for you’” (1 Corinthians 11:23-24). Jesus was broken for her. Jesus’ bones did not break (John 19:36; Exodus 12:46; Psalm 34:20), but His body did. He did writhe in pain. Jesus may not heal all our brokenness now, but He was broken so that the fractured world could be healed.

The Bible says God took on human flesh (John 1:1-3, 14) partly to experience suffering Himself. God, therefore, understands suffering, “not merely in the way that God knows everything, but by experience.”11 Jesus became fully human in every way so that He could be faithful and merciful, and provide rescue and forgiveness to people (Hebrews 2:17). The Bible may not completely answer the mystery of suffering and evil, but it does give an answer: Jesus. Amid the struggles and psychological storms of life, the cross of Christ is a column of strength and stability. It signals out to us in our fog: “I love you!” The cross is the lighthouse to our storm-tossed souls.

Christianity teaches that the Potter made the platter and was heartbroken over it breaking. So, because of His love for the platter, the Potter allowed Himself to be broken to fix the broken platter (John 3:16). The Bible does stop with the Potter being broken. The Bible concludes with resurrection. Jesus dies, yes. But He does not stay dead. The shattered shards are mended and whole. Jesus is the foretaste, and His rising proves that the whole world will be put back together.

Healed and Whole

The mathematician, scientist, and philosopher Blaise Pascal wrote this thought, which, at first, is a little confusing: “Who would think himself unhappy if he had only one mouth, and who would not if he had only one eye? It has probably never occurred to anyone to be distressed at not having three eyes, but those who have none are inconsolable.”

What does Pascal mean by this? He means that we only miss something if it’s missing. We only miss something if it’s gone. We don’t notice an absence of things that were never there. Hunger points to food, thirst points to water, and a sense of brokenness points to a previous wholeness. As Peter Kraft has said, “We suffer and find this outrageous, we die and find this natural fact unnatural.” Why do we feel this way? “Because we dimly remember Eden.”12

Within our very complaint against God, there is a pointer to God and the reality of Christianity. Christianity gives a plausible explanation as to how the brokenness of the world happened in space and time history. But it also gives us a credible solution; the Potter who made the world and died for the world, promises to one day fix the world.

Christianity gives a logically consistent explanation for the brokenness of the world. And it supplies the solution. We certainly long to be healed and whole. Every dystopia, true and fictional, starts with a desire for utopia. But inevitably dissolves into dystopia. Jesus, however, is not only all-powerful and thus able to bring about a different state of things, He is also all-good so He actually can bring about a utopia. He can heal and make the world whole.

The Bible says that the Potter who formed the platter will reform and remake it in the end. The shattered shards will be put back in place, and everything will be mended and whole. The last book of the Bible says this:

‘Look! God’s home is now among people! God will live together with them. They will be his people. God himself will be with them and he will be their God. God will take away all the tears from their eyes. Nobody will ever die again. Nobody will be sad again. Nobody will ever cry. Nobody will have pain again. Everything that made people sad has now gone. That old world has completely gone away.’ God, who was sitting on the throne, said, ‘I am making everything new!’ (Revelation 21:3-5)

For now, we make mosaics out of the shattered shards of life. We paint as best we can with the canvas and colors we have.

Conclusion

We started with a few questions. Here are a few to consider at the end. What if you are not the only one that has walked your path of pain? What if you are not the only one that has faced your terrible trauma? What if there was someone who, because of their experience, knowledge, wisdom, empathy, sympathy, and their own suffering of trauma, could relate to all that you have gone through? What if that person loved you? What if they wanted to help you heal from your pain and protect you? What if they would go to any length to free you from what you have suffered?

What if the problem of evil gives a plausible argument for the reality of Christianity? What if naturalism does not even have a way to believe in the reality of evil? What if we do not like God because of all the bad things in the world, but God Himself actually took the bad things of the world on Himself to fix the broken world?

What if Jesus was shattered so that one day you could be mended and whole? And what if He promises to help pick up the pieces and make a masterful mosaic?

Photo by Evie S.

- Peter Kreeft, Making Sense Out of Suffering. ↩︎

- As Christopher Watkin has said, “in a world without the sort of god the Bible presents, there is no necessary stability to reality because nothing underwrites or guarantees the way things are” (Biblical Critical Theory: How the Bible’s Unfolding Story Makes Sense of Modern Life and Culture, 225). ↩︎

- Watkin, Biblical Critical Theory: How the Bible’s Unfolding Story Makes Sense of Modern Life and Culture, 55. ↩︎

- As N. T. Wright has said, “The ‘problem of evil’ is not simply or purely a ‘cosmic’ thing; it is also a problem about me” (N. T. Wright, Evil and the Justice of God, 97). ↩︎

- Watkin, Biblical Critical Theory, 166. ↩︎

- Consider that “Physics can explain how things behave, but it cannot explain how they ought to behave. If the universe is the result of randomness and chance, there’s no reason to think things ought to be one way as opposed to another. Things just are.” (Michael J. Kruger, Surviving Religion 101: Letters to a Christian Student on Keeping the Faith in College, 116-17). ↩︎

- Peter Kreeft, Making Sense out of Suffering. ↩︎

- Ibid. ↩︎

- C. S. Lewis, Mere Christianity (London: Fontana, 1959), 42. ↩︎

- See Watkin, Biblical Critical Theory, 168. ↩︎

- D.A. Carson, How Long, O Lord?: Reflections on Suffering & Evil, 179. ↩︎

- Kreeft, Making Sense out of Suffering. ↩︎

Naturalistic evolution teaches that our sense of morality evolved

Imagine I gave you a pill that made you feel morally obligated to give me money… Kinda random but hear me out. After the pill wore off, what would you think of your moral conviction to give me money? Would you regret it? Question it? Probably both.

That’s what moral conviction is if we’re simply evolved creatures. Why? How is that so?

Naturalistic evolution teaches that our sense of morality evolved

Naturalistic evolution teaches that our sense of morality evolved. That is, our “moral genes” just happened to make us better suited for survival, and thus those with a moral characteristic passed on their “moral genes.” And so, we have morality. But, so the thought goes, just as the Neanderthals died out, morality could have died out. Or certainly, a different form of morality could have won out.

In fact, Charles Darwin says in The Descent of Man that if things had gone differently for humans they could have evolved to be like bees, where “females would, like the worker-bees, think it a sacred duty to kill their brothers, and mothers would strive to kill their fertile daughters.” The atheist Michael Ruse in his book, Taking Darwin Seriously: A Naturalistic Approach to Philosophy, says, “Morality is a collective illusion foisted upon us by our genes.”

So, if we’re simply evolved from monkeys, morality is the equivalent of taking a pill that makes us think certain moral convictions are right. But the reality would be different. We, based on this view, only have those convictions—whatever they are: treat people nice, don’t murder and maim, etc.—because we happed to evolve that way (“took the pill”).

Of course, just because the way that you arrived at a conclusion was wrong, does not mean that your conclusion was wrong. In a test where the answer is A, B, C, or D, I could just choose “C” because it’s my favorite letter. I may be correct in my answer, but I certainly don’t have a solid reason for believing in the validity of my answer. In fact, probability would say my answer is likely wrong.

Another problem with wholesale naturalistic evolution is if we believe it explains everything then it in some ways explains nothing. Gasp. Yeah, that’s not a good thing.

If evolution explains morality, then I’m moral because of evolution which at least in some ways undercuts morality. Some people even say that religious people, like people that believe in Jesus, are religious because they evolved that way. Believing in a higher power brought some type of group identity which led tribes of our ancestors to be more likely to protect each other and thus survive and pass on their genes. And so, religion is the result of random mutational chance.

In fact, you could argue all of our thinking processes are the result of evolution. We’re just matter in motion. We’re all just responding to random whims. From belief in morality to belief in evolution, we’re just evolved to think this way… We can’t do anything about it. It’s programmed into us. It’s the pill we were given…

But if all this is a pill we’re given—what we’ve randomly evolved to think—what should we think?… Isn’t all our thinking just built into us through evolutionary processes?…

Alternatively, Christians believe that humans are created with an innate moral sense.

So, it seems morality is either a fiction with no basis in reality or God created us and explains reality—explains why we have an innate sense that we should treat people nice and not murder and maim.

There are big implications for either view. What is your view? And why?

Somewhat Random Reflections on Knowledge

Here’s some somewhat random reflections on knowledge if you’re interested…

How Can We Know Anything at All?

Wow. That is a super big question. And it’s a question that some people are not asking at all. That’s problematic. And in some ways ignorant. However, others are asking that question but they’re asking it in a proud way. That’s also problematic. And ignorant.

Let me ask you a question, how do you know your dad is your dad? Well, some of you will say, “He’s just my dad. He’s always been my dad. I’ve always known him as my dad.”

But I could say, “But, how do you know you know for sure he’s your dad?”

Others will answer, “I know he’s my dad because my mom told me.” But how do you know your mom’s not lying? Or, how do you know she knows the truth?

Perhaps the only way to know your dad is actually your biological dad is through a DNA test. But could it be the case that the DNA clinic is deceiving you? Is it possible that there’s a big conspiracy to deceive you? What if you are actually part of the Truman Show? Everything is just a big hoax for people’s entertainment?… How could you know without a shadow of a doubt that that’s not happening?

You really can’t. Not 100%.

We Can’t Know Everything

We, I hope you can see, can’t know everything. There’s a healthy level of skepticism, just as there is healthy humility.

Also, if we think our knowledge must be exhaustive for us to have knowledge, we will never have knowledge. And we will be super unproductive. I, for one, would not be able to go to the mechanic. And that would be bad.

Our knowledge is necessarily limited. We may not like it but that’s the cold hard truth, we must rely on other people. We must learn from other people. There’s a place for us to trust other people. Of course, we are not to trust all people or trust people all the time. But we must necessarily rely on people at points.

Philosophy and the History of Careening Back and Forth Epistemologically

John Frame, the theologian and philosopher, shows in his book, A History of Western Philosophy and Theology, that the history of secular philosophy is a history of humans careening back in forth from rationalism to skepticism and back again. One philosopher makes a case that we can and must know it all, every jot and title. And when they’re proven wrong, the next philosopher retreats to pure epistemological anarchy, claiming we can’t know anything at all. Again, when it’s found out that that view is wrong and we can in fact know things, we swing back the other way. And so, the philosophical pendulum goes and we have people like Hume and people like Nietzsche.

The history of philosophy shows that we should be both skeptical about rationalism and rational about skepticism. Both have accuracies and inaccuracies. Which helps explain the long life of both.

The Bible and Knowledge

The biblical understanding of knowledge takes both rationalism and skepticism into account and explains how both are partly right and partly wrong. And it explains that though we may not be able to know fully, we can know truly. It also explains that there are more types of knowing than just cognitive and rational. The Bible not surprisingly understands who we are anthropologically and so is best able to reveal the whole truth epistemologically.

The Bible also understands that there is experiential knowing, tasting—experiencing something—and knowing something to be true on a whole different level than mere cognitive knowing. When the Bible talks about “knowing” it’s intimate, tangible, and experiential knowing. For example, it says Adam “knew” his wife and a child was the result of that knowledge. That, my friends, is not mere mental knowledge. It’s lived—intimately experienced—knowledge. It’s knowledge that’s not available without relationship.

Job says it this way, I’ve heard of you but now something different has happened, I’ve seen you (Job 42:5). Jonathan Edwards, the philosopher and theologian, talked about the difference between cognitively knowing honey is sweet and tasting its goodness. It is a world of difference. The Bible is not about mere mental assent. It is about tasting. Knowing. Experiencing. Living the truth.

The Bible says and shows that Jesus is Himself is the way, the truth, and the life. Jesus is what it means to know the truth. He is the truth and shows us the truth. He is truth lived, truth incarnate.

The Bible communicates that some people don’t understand, don’t know the truth. There’s a sense in which if you don’t see it, you don’t see it. If it doesn’t make sense, it doesn’t make sense. The Bible talks about people “hearing” and yet “not hearing” and “seeing” and “not seeing.” Some people believe the gospel and the Bible is foolishness (1 Cor. 2:14).

How Should Christians Pursue Knowledge?

First, our disposition or the way we approach questions is really important.

How should we approach questions? What should characterize us?

Humility! Why? Because we are fallible, we make mistakes. However, God does not. Isaiah 55:8-9 says, “For My thoughts are not your thoughts, neither are your ways My ways, declares the LORD. For as the heavens are higher than the earth, so are My ways higher than your ways and My thoughts than your thoughts.”

Also, kindness, patience, and understanding are an important part of humility and asking questions and arriving at answers. So, “Faith seeking understanding,” is a helpful and common phrase.

Second, where do we get answers from?

Scripture. Why is this important? Again, I am fallible and you are fallible, that is, we make mistakes. And how should we approach getting those answers? Are we above Scripture or is Scripture above us? Who holds more sway? Scripture supplies the truth to us; we do not decide what we think and then find a way to spin things so that we can believe whatever we want…

Third, community is important.

God, for instance, has given the church pastor/elders who are supposed to rightly handle the word of truth and shepherd the community of believers. We don’t decide decisions and come to conclusions on our own. God helps us through Christ’s body the Church.

Fourth, it is important to remember mystery.

We should not expect to know all things. We are… fallible. So, we should keep Deuteronomy 29:29 in mind: “The secret things belong to the LORD our God, but the things that are revealed belong to us and to our children forever, that we may do all the words of this law.” There are certain things that are revealed and certain things that are not revealed.

Fifth, our questions and answers are not simply about head knowledge.

God doesn’t just want us to be able to talk about theology and philosophy. Deuteronomy 29:29 says, “that we may do…” So, God also cares a whole lot about what we do. Knowledge is to lead to action. We are to be hearers and doers.

What explains the contradiction of humanity?

What explains the contradiction of humanity?

Can an outside hand reach into the fishbowl of our universe?

Can an outside hand reach into the fishbowl of our universe?

Newton, a scientist that also happened to be a fish, was a keen observer of the ecology of the fishbowl. He was surprised to observe regular patterns in his fish universe. But he did.

For example, Newton observes that food daily falls upon the surface of the water at the same time each day. It is a law of nature. It’s just the way the world is.

Newton observes other natural phenomena like the temperature of the water. He further notes that each death of a goldfish results in a distant flushing noise and then in reincarnation of that goldfish. Newton, awestruck by his discoveries, publishes his findings in his magnum opus entitled Fishtonian Laws.

Many read his groundbreaking work and are convinced that the laws of the fishbowl are unassailable. After all, the patterns observed have always been that way and so always will be that way. No outside source can act within the fishbowl. The reality is food appears every day and as a goldfish dies, a new one appears. That is the unbroken chain of events we observe. That is the way it’s always been. How could it be different? Who or what could act on these laws of nature?

We are in a closed system; the aether of the universe—in which we live, move, and have our being—is constrained by an invisible force. There is an unknown unobservable wall that keeps us from knowing what is outside nature, what is outside the physical universe. There is no way for us to know the metafishbowl.

In the post-Fishtonian world, there were still whispers of the metafishbowl—of the supernatural hand of God—but most of those stories were dismissed as baseless dreams. After all, even if there were a God that set up the fishbowl, he no longer acts in the fishbowl. Such a being is wholly other and transcendent and would not care about lowly fish.

Everything just goes on swimmingly by itself. We shouldn’t expect an outside hand, right?… There is no reason to think an outside being or force could act within our world.

Or, does something smell fishy about this story?

If God created the universe, what created God?

We, as sentient and at least somewhat intelligent humans, exist. That’s not debated by most people. How, however, did we get here? Where or who did we come from? And if God created us, who or what created God?

Panspermia

Some have speculated that we got here through panspermia or even directed panspermia.[1] Panspermia is the hypothesis that microorganisms were seeded to our planet through meteoroids, comets, asteroids, or even from alien life forms. That just moves the question back. Where then did life come from (to say nothing of matter)?

Interestingly, some have speculated what it would take for us to seed life to another planet by blasting off a rocket with microorganisms onboard. Some believe we could carry out a “Genesis” mission to an uninhabited planet within 50 to 100 years.

Of course, the mission would require a lot of really smart people working in coordination with a lot of really smart people. And it would cost a lot of money and use things like ion thrusters and really advanced robots. So, starting with life and intelligence, it may be possible to seed life to other planets (assuming they are fine-tuned to support life). But again, this just pushes the question back and proves the need for intelligent design.

Multiverse or many worlds hypothesis

Another hypothesis to explain the origin of life on earth (specifically intelligent life on earth) is the multiverse theory.[2] Yes, this should remind you of all the crazy stuff that happens in Spider-Man: Into the Spider-Verse. This theory is interesting and problematic for a number of reasons. It’s more science fiction than fact.

- It is, by far, not the simplest explanation. This is problematic (see: Occam’s razor).

- It’s nonsensical. One could then postulate that there is a near-infinite number of you, or of Loki. Loki was a cool show but the questions multiply as the “Lokis” multiply.

- There’s nothing that we have observed that would lead us to logically conclude that there is or is likely a multiverse (it seems, rather, that those arguing for this position are just frantically trying to get away from the reality of the existence of God[3]).

If God created the universe, what created God?

Here are the options:

- The universe somehow sprang from absolute nothingness completely on its own.

- The universe inanimate has existed eternally and that something somehow exploded and eventually led to the life forms we have now.

- The universe was created by a powerful and eternal Entity.

Each of those options is honestly hard to fathom. Which makes the most sense?

The universe somehow sprang from absolute nothingness completely on its own.

This is not something we really observe. In our experience and observation, something does not come from nothing. If even a simple pool ball is rolling on a pool table we assume it was set in motion by something. We don’t assume it moved although no force whatsoever acted upon it (What about quantum particles?[4]).

There’s a story about a scientist making a bet with God. The scientist bets God that he can create life. The scientist grabs some dirt and sets off to work. When a voice from heaven said, “Get your own dirt!”

“It is a vain hope to try to give a physical account of the absolute beginning of the universe. Not only must the creation event transcend physical law, it must also,… transcend logic and mathematics and therefore all the scientific tools at our disposal. It must be, quite literally, supernatural.”[5]

The universe has eternally existed.

If the expansion of the universe were an old VHS video that you could reverse, you’d see the contraction of the universe into an infinitesimally small singularity—back into the nothingness from which the universe sprang.[6] Thus, the Big Bang actually matches with what Scripture says. That is, the universe—all the matter that is—came into being at a finite time, ex nihilo, out of nothing.

The universe has not existed eternally.

The universe was created by a powerful and eternal Entity.

It makes sense to say, doesn’t it, that anything that begins to exist must have a cause of its existence?[7] I think that makes a lot of sense. I mean a pool ball on a pool table isn’t going to move unless someone or something causes it to move.

This is especially the case when we consider the extreme fine-tuning necessary to allow for life, especially intelligent life. “On whatever volume scale researchers make their observations—the universe, galaxy cluster, galaxy, planetary system, planet, planetary surface, cell, atom, fundamental particle, or string—the evidence for extreme fine-tuning for life’s sake, and in particular for humanity’s benefit, persists.”[8]

God is the Uncaused Cause, the Unmoved Mover. God is. He is the Creator.

But then, who or what created God?

Anything that begins to exist must have a cause of its existence. The thing with God is, He did not begin to exist. He has always existed. Therefore, He needs no cause or creator. He is the Creator.

“The Cause responsible for bringing the universe into existence is not constrained by cosmic time. In creating our time dimension, that agent demonstrated an existence above, or independent of, cosmic time… In the context of cosmic time, the causal Agent would have no beginning and no ending and would not be created.”[9]

This is, in fact, what the Bible says about the LORD God. It says, “the LORD is the everlasting God, the Creator of the ends of the earth” (Is. 40:28) and it says, “In the beginning, God created the heavens and the earth” (Gen. 1:1 cf. Ps. 136:5; Is. 45:18; Col. 1:16).

The universe has not always existed. Instead, “the universe was brought into existence by a causal agent with the capacity to operate before, beyond, unlimited buy, transcendent to all cosmic matter, energy, space, and time.”[10]

God revealed Himself to Moses as: “I Am who I Am” (Ex. 3:14). God is the One who Is. He is the Existing One. He is the One who is beyond and before time and matter. And as such, He is able to create time and matter.

If God’s existence doesn’t need an explanation then why should the universe’s existence need an explanation?

“This popular objection is based on a misconception of the nature of explanation. It is widely recognized that in order for an explanation to be the best, one need not have an explanation of the explanation (indeed, such a requirement would generate an infinite regress, so that everything becomes inexplicable). If astronauts should find traces of intelligent life on some other planet, for example, we need not be able to explain such extraterrestrials in order to recognize that they are the best explanation of the artifacts. In the same way, the design hypothesis’s being the best explanation of the fine-tuning does not depend on our being able to explain the Designer.”[11]

How should we respond to the One who created the universe?

That’s a big question. But, I’ll take it further, how should we respond if the Christian understanding of God is correct? What if the Programmer coded Himself into the program like the Bible talks about?

If what Scripture says of the Creator entering His creation is true, as I believe it is, then I think it clearly follows that we should be amazed and submit to the One who has shown Himself to be the Lord.

We must all, however, make that choice on our own. I can’t make it for you. But I, for one, am awed and astounded that the Creator would enter His creation to rescue His creation.

Not only that but the Creator was crucified (see Col. 1:15-20). As Jesus was making purification and propitiation for sin by bearing our sin on the cross, He was simultaneously upholding the universe by the word of His power (Heb. 1:2).

How should we respond to the One who created the universe and yet loves us?! I believe we should respond in reverent worship:

Notes

[1] E.g. Francis Crick, Life Itself: Its Nature and Origin (New York: Simon & Schuster, 1981).

[3] “The many worlds hypothesis is essentially an effort on the part of partisans of the chance hypothesis to multiply their probabilistic resources in order to reduce the improbability of the occurrence of fine-tuning” (J.P. Moreland & William Lane Craig, Philosophical Foundations for a Christian Worldview [Downers Grove: InterVarsity, 2003], 487). Ironically, “the many worlds hypothesis is no less metaphysical than the hypothesis of a comic designer” (Moreland & Craig, Philosophical Foundations for a Christian Worldview, 487).

[4] “There is no basis for the claim that quantum physics proves that things can begin to exist without a cause, much less that [the] universe could have sprung into being uncaused from literally nothing” (Moreland & Craig, Philosophical Foundations, 469). Even if one follows the Copenhagen interpretation of quantum physics, “particles do not come into being out of nothing. They arise as spontaneous fluctuations of the energy contained in the subatomic vacuum, which constitutes an indeterministic cause of their origination” (Ibid.). This very brief explanation is helpful: https://www.linkedin.com/pulse/quantum-field-theory-what-virtual-particles-laymans-terms-javadi/ and also see: http://atlas.physics.arizona.edu/~shupe/Indep_Studies_2015/Homeworks/VirtualParticles_Strassler.pdf

[5] David A. J. Seargent, Copernicus, God, and Goldilocks: Our Place and Purpose in the Universe, 114.

[6] A better illustration would actually be a balloon losing its air. When considering the expansion of the universe it’s amazing to consider that eventually the universe will grow dark because the speed of the expansion of the universe will eventually be too great for us to observe our cosmic surroundings.

[7] “Everything restricted to the cosmic timeline must be traceable back to a cause and a beginning” (Hugh Ross, Why The Universe Is The Way It Is, 132).

[8] Ross, Why The Universe Is The Way It Is, 124. See e.g. Hugh Ross, “Fundamental Forces Show Greater Fine-Tuning” https://reasons.org/explore/publications/connections/fundamental-forces-show-greater-fine-tuning, Fazale Rana, “Fine-Tuning For Life On Earth (Updated June 2004)” https://reasons.org/explore/publications/articles/fine-tuning-for-life-on-earth-updated-june-2004, and Seargent, Copernicus, God, and Goldilocks, 121-127.

[9] Ross, Why The Universe Is The Way It Is, 132.

[10] Ibid., 131.

[11] Moreland & Craig, Philosophical Foundations, 487.

*Photo by Tyler van der Hoeven

Does the concept of justice even make sense today?

Humans, I believe, want justice. I believe that is a natural and good desire that is innate within us. Where, however, does the concept of justice come from? How do we know what is right and what is not right? Does the concept of justice even make sense today?

The theme of the day is, “Have it your way,” “Do what’s right for you.” It’s, “You be you.” It’s, “You be happy.” It’s, “Free yourself from the oppressive shackles of society, family, and really any expectation at all.”

Don’t discard what’s valuable

Now, to use a disturbing and fitting analogy, we often sadly throw the baby out with the bathwater. No matter what the baby or the bathwater is. We throw them both out. I don’t think we should completely throw out the baby (of course!). I think there’s some definite truth to “doing what’s right for you,” “being yourself,” “being free from oppressive shackles,” “being happy,” and even “having it your way.”

But, does that mean that there’s not an actual right way to live? Does that mean that the actual best version of yourself might not require humility and the admitting of wrong? Do all restrictions have to be considered oppressive shackles (perhaps a train is most free on the tracks!)?

If there is actual truth and justice it might not just convict the bigoted and intolerant, it might convict me of wrong. If there is such thing as actual wrong, I’m not immune from justice’s scale. I myself could be found and wanting. Perhaps it could be found out that me “having my own way,” is not the way, is not right?

What if there is no actual truth or justice?

If, however, “moral truths” are nothing more than opinions of an individual and are thus infallible then what grounds is there for justice? If we believe in “truth” by majority—truth by popular consensus, then which majority, on which continent, at which time in history? And how is this actually very different than Nazism and “might makes right” morality?

People’s cry for justice would then be nothing more than mere power grabs, people asserting themselves over others. Crying out for justice would be nothing more than enforcing one’s own or a group’s preference on others. That does not seem very tolerant. “Who are you or who are y’all to enforce your opinion on me?”

When we say we can’t actually know what is truly right or wrong it undermines the concept of justice.[1] If we can’t truly know what is just how then can we have justice? If we can know what is just, how? Where do we get this concept of justice from?

So, is there actual truth and justice?

Can we know? Or, are we left in the dark to grope our way?

I believe our flourishing as a society is bound up with the truth. Our happiness is collectively tied to knowing how to live and living that way.

If the majority collectively says there is no actual truth then we will walk in epistemological darkness. And in the darkness, we will fall. We will trip into a thousand blunders.

If we say we cannot know what is truly just, then justice will wane. If there is no just, there is no justice. If there is no conviction that we are at least sometimes wrong, there will be no conviction that anyone is wrong. But, if there is the conviction that we are sometimes wrong, there must be a confession that there is actual truth.

There is a price to moral “freedom.” That cost is to shut the lights off and to walk in darkness.

I believe the concept of truth and justice makes sense today

I believe truth is precious. Although truth at times has rough edges. And at times I collide into it’s jagged ends.

“The modern man in revolt has become practically useless for all purposes of revolt. By rebelling against everything he has lost his right to rebel against anything” (G.K. Chesterton).

“If you see through everything, then everything is transparent. But a wholly transparent world is an invisible world. To ‘see through’ all things is the same as not to see” (C.S. Lewis).

“Believe in truth. To abandon facts is to abandon freedom. If nothing is true, then no one can criticize power, because there is no basis on which to do so. If nothing is true, then all is spectacle. The biggest wallet pays for the most blinding lights” (Timothy Snyder, On Tyranny).

So, truth sometimes tears into us and sometimes hurts because it’s actually there. We get hurt when we act like it’s not. Because it is. We intuitively know this, because we care about justice. We care about people “getting what’s coming to them.” Because the concept of justice makes sense even today?

How, however, can we know the truth? And what hope is there for us who have been measured and found wanting on the scales of justice?

___

[1] Steve Wilkens and Mark L. Sanford, Hidden Worldviews: Eight Cultural Stories That Shape Our Lives, 95.

Awaking Relevance Introduction

How should we live and why?

This is written for those who think church is bigoted and bad. It’s written for those who are bitter and done. It’s honestly specifically written for one of my friends. I want to awake them and you to the relevance of Christianity. Will you take some time to consider some important questions with me?

My question over all of this project is, does Jesus, who the Bible claims to be the Messiah, matter? We will not come at that question straight on. Instead, we will consider that question by asking other very important questions. Questions that are important but are often left unasked. Questions that close in on us and surround us and squeeze us. Questions that are there lurking.

Questions about death. About whether or not the world is enchanted. Questions about science and satisfaction. And morality and meaning.

You will answer these questions. We all have to. Will we, however, ask them? Will we think through them? Will we answer them honestly? And thoughtfully and thoroughly?

Socrates, the old and famous philosopher, is reported as saying, “The unexamined life is not worth living.” I personally think that Socrates exaggerated. I think life is worth living even if we don’t think about it. But, I do believe that it’s much better to live an examined life. And it’s much more honest and genuine too.

So, will you consider these questions? Will you ask them and find the real you? Will you find out what you really believe? Will you fight the façade and live the most honest and genuine life you can?

It’s better to consider these questions before it’s too late. To truly ask and answer: Does Jesus matter?—then to assume He does, if doesn’t. The opposite follows too. What if we assume Jesus doesn’t matter when He does? As the adage goes, if we ASSUME it makes an ASS out of U and ME. And as C.S. Lewis said, “Christianity, if false, is of no importance, and if true, of infinite importance, the only thing it cannot be is moderately important.”

If Jesus is not really God in flesh, as the Bible claims, then “what conceivable relevance may the teachings and lifestyle of a first-century male Jew have for us today, in a totally different cultural situation?”[1] So, does Messiah Jesus matter? Consider that question with me through the lens of these other questions. Perspective often allows us to see something we didn’t before. That’s our goal. To gain perspective so that we can come full cycle and be in a better place to ask the question “does Messiah Jesus matter?”

I’m sure it’s apparent to you at the outset, but I’m convinced He does matter. I believe He matters more than the oxygen in my lungs. I want to be totally honest with you. Also, something in the back of my head informing a lot of what I write is a verse from the Bible. It has been very meaningful and challenging to me. It says, “How long will you go limping between two different opinions, if the LORD is God, follow Him; but if Baal, then follow him.”[2]

I want you to be truly convinced one way or the other. To tweak Socrates’ wisdom: the unexamined life is not consistent.

I believe we should examine our convictions about what is true, right, good, and beautiful, and then seek to live consistently with our convictions in every area of our lives.[3]

A couple of years ago my family and I lived outside of Washington, DC. I was grabbing tacos with a friend at a really good local chain. I believed I was at the right place. it was the right taco chain after all. But my friend, who was not normally late, was not there. So I called him. He said he was sitting in the front of the restaurant and waiting for me. But I was there and sitting in the front and waiting for him. And he was nowhere to be found.

I believed I had the right spot, that’s why I was there. But I was wrong. I was at the right taco establishment but not the right location. So, you see, when we get little things wrong, even if we get a lot right, it can have a big impact. Even a devastating impact.

“Little, everyday decisions will either take you to the life you desire or to disaster by default… Stray off course by just two millimeters, and your trajectory changes; what seemed like a tiny, inconsequential decision then can become a mammoth miscalculation.”[4]

When we believe something, like the place we’re meeting a friend, it leads to a corresponding action: going there. We can think we’re right, and even have reasons for thinking we’re right, but still be wrong. Because beliefs inevitably impact our actions it’s important that we be reasonably sure our beliefs are correct.

Of course, my belief in the correctness of the taco joint location is less impactful than my belief about many other things. My point, however, is that even less meaningful beliefs have an impact so how much more beliefs about things that we deem of much higher importance?!

William Kingdon Clifford, the philosopher and mathematician in his essay “The Ethics of Belief” said, “It is wrong always, everywhere, and for anyone to believe anything upon insufficient evidence.”[5] Or, as the philosopher and English writer, G.K. Chesterton said, “An open mind is like an open mouth: useful only to close down on something solid.”

Our beliefs matter. They have an impact on our life and the lives of others. It is important that we consider what we believe and why. We’d be wise to remember, “It doesn’t matter how smart you are unless you stop and think.”[6]

We see this through social media. It’s easy to get duped by fake news. It’s too easy for people to take the bait and believe lies. It’s too easy for people to hype conspiracy theories.

We don’t want to be guilty of living the unexamined life. We don’t want to live a conspiracy theory. We don’t want to build our foundation on the equivalent of fake news. Fake news is no foundation.

If you’re like me, however, you have a built-in mechanism that is like a gag reflex to certain serious questions. I remember when my parents were separated as a kid before they got divorced. We had various “family meetings.” I remember my brother’s and I being the kings of diversion.

We were like the squirrel in the movie “Hoodwinked,” except our mission was distraction. We would wedge in any funny comment. Anything to lighten the mood. We didn’t want to hear and deal with the harsh realities in front of us.

I’m older now. Obviously. But sometimes my inner hyperactive squirrel wants to take over when I’m in a serious conversation. I want to run. I want to do anything to escape.

If it’s not my inner squirrel, sometimes it’s my inner lawyer that wants to come out and defend myself and throw the book at the other party. I don’t want to hear. I want to yell. I want to prove myself in the right.

The way of my inner squirrel and the way of my inner lawyer is not the way of wisdom. I need to listen. I need to learn.

I need to question some of my beliefs. I need to weigh them to see if I really have good reasons for holding them.

Distractions can be devastating. Want if I have a concern that I have cancer but I fear what that would mean. So, I just keep putting it off. I don’t deal with it. I don’t get checked out.

There can come a time when it’s too late. The damage has been done.

I challenge you to consider this question with me: How should we live and why? As well as the questions that accompany this important question. The philosopher Peter Kreeft said,

“If we are at all interested in the question of how to live (and if we are not, we are less than fully human and less than fully honest), then we too must… ask questions. They are inherent in the very structure of our existence.”

Thoughts and questions are important. They shape our destiny. As Samuel Smiles said,

As I alluded to, this series is called Awaking Relevance because I’d love to have you awake to the relevance of Jesus. I’d love for you to come away seeing that Messiah Jesus matters. I’d love for you to find that Jesus shows us a meaningful way to live as well as the motivation for doing so.

But, perhaps you’ll never agree that Jesus matters. Perhaps this will be a decisive death to the relevance of Jesus for you. Regardless, I think it makes sense to really weigh it out. After all, Jesus had and has a big following. He had an impact.

Should He have an impact on your life? That’s what will consider through various questions in the following posts. I hope you will join me. I hope you will examine your beliefs. I hope you will consider: How should we live and why?

Truth is a shape sorter

There is a certain way the world is, whether we like it or not. I think of a shape sorter for example. There are certain places where things fit and certain places where they don’t fit. A square is a square and goes in a square hole, not in a triangle hole.[1]

We could imagine doing a shape sorter box blindfolded. It would be difficult. We would have to feel our way to what was right. And imagine if someone was getting in our face and trying to distract us and give us the wrong pieces to put in the wrong spot… It would be extra difficult. It would still be clear that there’s a correct place for the pieces—i.e. a correct way the world is to function—yet it would be difficult to make things function the way they are supposed to without the correct guidance.

We can try and go against this reality but it’s going to be problematic. Things won’t fit. People all the time say things like: “Have it your way,” “Make your own reality.” But that doesn’t mean you actually can.

In John 18, Pilate speaking to Jesus said: “What is truth?” Ironically, Pilate was talking to Truth Himself (Jn. 14:7). That was over 2,000 years ago.

The existence of truth has been questioned for a long time.

Pilate said, “What is truth?”

People today say, “We make our own truth…”

Deceit is the bastion of the wicked.

The absence of truth is a work of Satan. It is a work of darkness and brings darkness (and is itself a defilement). Satan is the father of lies and there is no truth in him (Jn. 8:44).

Satan is the archenemy of God. God hates untruth (Is. 59:4, 14-15).

When truth is not followed or truth is doubted it brings an avalanche of evil and destruction. Untruth leads to (or is) injustice. Untruth is far from the good of God’s character and design.

Thus, truth is vital. People are destroyed when they lack right knowledge (Hosea 4:6, 14).

Truth is the seal of the Savior and is (or should be!) the seal of the saved.[2]

We must obey the truth (Gal. 5:7) knowing that the truth sets free (Jn. 8:32), sanctifies (Jn. 17:17), and purifies (1 Pet. 1:22). Thus, the truth must be preserved (cf. Gal. 2:5). Scripture, the truth, must be treasured (Ps. 119:105; Jn. 17:17).[3]

What we do matters. And that’s good news.

Yesterday I posted a few thoughts about Matthew 16:27 which says “the Son of Man is going to come with His angels in the glory of His Father, and then He will repay each person according to what he has done.”

For a lot of people that may seem very heavy and discouraging. For me, it’s good news. It’s good news because it means there’s meaning. What we do matters.

It makes me think of Albert Camus’s “The Myth of Sisyphus.” In “The Myth of Sisyphus,” Sisyphus has to carry a huge rock up a hill and you know what happens once he does? It rolls right back down the hill… And again and again and again… Basically, Camus is saying life is meaningless and absurd.

And that reminds me of another philosophical work, the book of Ecclesiastes from the Bible. One of the reoccurring phrases in that book is “vanity of vanities.” Is all meaningless? Does what we do matter?

The Bible answers with a resounding “Yes!”

For someone who has wrestled with depression because of perceived purposelessness, it’s good news that what we do matters. It adds pep and purpose to my life… Even if it’s a heavy truth, I’ll take it because it means our lives have weight.

The fact that Jesus will repay each person according to what they have done adds huge significance to our lives. “We’re playing for keeps,” so to speak. Life is the real thing. We should live and enjoy it and we should love God and others. That’s what Ecclesiastes concludes with.

So, I’m thankful for the good news that what we do in life matters. I’m especially mindful of that on the day after Martin Luther King Jr. Day. Martin and the Million Man March mattered. It mattered and racism matters.

It matters that MLK was killed. It matters that MLK peacefully fought for the sanctity of blacks and all people. It matters for a lot of reasons. But for one, it matters because people will give an account for their racism, acts of violence, and even every careless word (Matthew 12:36).

So, as I said, this is heavy and hard. It’s not an easy pill to swallow but it is the medicine we need. We can’t lash out and attack and think it doesn’t matter. Our every action is riddled with significance. That truth, however, shouldn’t cripple us, it should cause us to fly to Jesus who is both our Savior and Sanctifier.

When the options are laid out in front of me, I’ll take actual meaning and significance every time. I don’t want the poisoned sugar pill that says what we do doesn’t really matter. I’ll take the truth even if it’s bitter.

What we do totally matters. It’s hard in some ways to hear that but the alternative is to say it doesn’t matter. And that would be saying nothing matters, there is no meaning.

To close, it seems there are three options:

1) Be crushed by the utter meaninglessness of life (e.g. give up, don’t care) or…

2) be crushed by the utter meaning of life (e.g. try to own everything, try to be the great rescue yourself) or…

3) trust Christ. Christ says there’s meaning and He says there’s hope. What we do matters and we’ve all failed. He, however, didn’t throw in the towel on us. He took up a towel and lived as a servant. He did all the good we should’ve done and didn’t do the bad. And yet He was crushed for us but not under the weight of meaning or meaninglessness but on a cross.

Jesus finished where we bailed, He succeeded where we failed. He’s always right and we’re often wrong. He has a perfect record and He offers it to us.