Why read? An argument for the importance of reading

Why read? Why am I committed to reading? For one, words matter. They matter to me and they mattered to Jesus and Paul too. I think words and reading should matter to you too.

Jesus read

Jesus apparently read or at least retained what He heard as a kid. He listened to the teachers and asked them questions and “all who heard Him were amazed at His understanding and His answers” (Lk. 2:47). So, words mattered to Jesus and especially God’s words.

When Jesus was tempted in the wilderness, He fought off the temptation by quoting Scripture (Matt. 4). Jesus clearly knew the Scriptures. He quoted from Deuteronomy chapter 6 verse 13, verse 16, and chapter 8 verse 3.[1]

Jesus read in the in the synagogue (Lk. 4:16) as was the custom on the Sabbath (Acts 15:21).

Paul read

Paul in Romans 3:10-18 quotes from ten different passages. And he did it from memory. It is unlikely that he would have looked up those passages in a nearby scroll. He certainly didn’t look it up in a concordance in the back of his Bible. No. He would have read those passages and memorized them. Scripture, however, was apparently not the only thing that Paul read and could quote. He also quoted popular poets (Acts 17:28).

Paul was in prison in Rome and he was writing his dear friend Timothy. He asked Timothy for a few items. First, we see he wants him to come before winter (2 Tim. 4:21) and bring his coat. Second, we see the importance of reading along with warmth, Paul wants his books and parchments too (2 Tim. 4:13).

Reading was important for the Apostle Paul.

You should too

Reading allows us to learn and glean from people in places and times we otherwise wouldn’t. Reading can facilitate wisdom. C.S. Lewis talks about the importance of prioritizing time-tested books.

I think there is a lot of wisdom in what Lewis said. I think our first priority should be the reading of Scripture. The Bible is the best-selling book of all time and the most translated book of all time. And Scripture gives us “the words of eternal life” (Jn. 6:68).

So, read books but especially read the Bible. Reading is important because God had revealed Himself and His will through revelation.

How to read more?

The number one advice I have is to prioritize reading. And deprioritize other lesser things, like social media. If reading is important, make sure it’s important in practice. Also, check out my advice “10 Ways to Read More Books in 2021.”

Read. Jesus and Paul the Apostle did.

Notes

[1] It’s important that we realize that the tempter also knows Scripture. In Matthew 4:6 the tempter quotes from Psalm 91:11 and 12 to try to cause Jesus to sin.

*Photo by Seven Shooter

10 takeaways from Vivek H. Murthy’s book Together

Being connected in community is important. Murthy’s book, Together: The Healing Power of Human Connection in a Sometimes Lonely World, concurs. Below are some quotes I appreciated from his book.

“The values that dominate modern culture… elevate the narrative of the rugged individualist and the pursuit of self-determination. They tell us that we alone shape our destiny. Could these values be contributing to the undertow of loneliness” (Vivek H. Murthy, Together, p. xxi).

“Social connection stands out as a largely unrecognized and underappreciated force for addressing many of the critical problems we’re dealing with, both as individuals and as a society. Overcoming loneliness and building a more connected future is an urgent mission that we can and must tackle together” (Murthy, Together, p. xxvi).

“People with strong social relationships are 50 percent less likely to die prematurely than people with weak social relationships… weak social connections can be a significant danger to our health” (p. 13).

“Few of us challenge our cultural norms, even when their influence leaves us feeling lonely and isolated” (p. 95).

“Building… bridges for connection may never have been more important than it is right now” (p. 96).

“If you ask people today what they value most in life, most will point to family and friends. Yet the way we spend our days is often at odds with that value. Our twenty-first-century world demands that we focus on pursuits that seem to be in constant competition for our time, attention, energy, and commitment. Many of these pursuits are themselves competitions. We compete for jobs and status. We compete over possessions, money, and reputation. We strive to stay afloat and to get ahead. Meanwhile, the relationships we claim to prize often get neglected in the chase” (p. 98).

“Social media… fosters a culture of comparison where we are constantly measuring ourselves against other users’ bodies, wardrobes, cooking, houses, vacations, children, pets, hobbies, and thoughts about the world” (p. 112).

“Many factors play into… polarization, social disconnection is an important root cause” (p. 134).

“Even as we live with increasing diversity, it’s easier than ever to restrict our contact, both online and off, to people who resemble us in appearance, views, and interests. That makes it easy to dismiss people for their beliefs or affiliations when we don’t know them as human beings. The result is a spiral of disconnection that’s contributing to the unraveling of civil society today” (p. 134).

“When I think back on the patients I cared for in their dying days, the size of their bank accounts and their status in the eyes of society were never the yardsticks by which they measured a meaningful life. What they talked about were relationships. The ones that brought them great joy. The relationships they wish they’d been more present for. The ones that broke their hearts. In the final moments, when only the most meaningful strands of life remain, it’s the human connections that rise to the top” (p. 284).

*Photo by Robert Bye

Quotes from Richard Bauckham’s The Theology of the Book of Revelation

Here are ten quotes from Richard Bauckham’s book, The Theology of the Book of Revelation, that especially stuck out to me. And if you’re interested in eschatology (the doctrine of last things) you can also see my post “Eschatology and Ethics.”

“Revelation provides a set of Christian prophetic counter-images which impress on its readers a different vision of the world… The visual power of the book effects a kind of purging of the Christian imagination, refurbishing it with alternative visions of how the world is and will be” (Richard Bauckham, The Theology of the Book of Revelation, p. 17).

“Creation is not confined for ever to its own immanent possibilities. It is open to the fresh creative possibilities of its Creator” (Bauckham, The Theology of the Book of Revelation, p. 48).

“A God who is not the transcendent origin of all things… cannot be the ground of ultimate hope for the future of creation. It is the God who is the Alpha who will also be the Omega” (Bauckham, The Theology of the Book of Revelation, p. 51).

“The polemical significance of worship is clear in Revelation, which sees the root of the evil of the Roman Empire to lie in the idolatrous worship of merely human power, and therefore draws the lines of conflict between worshippers of the beast and the worshippers of the one true God” (p. 59).

“Who are the real victors? The answer depends on whether one sees things from the earthly perspective of those who worship the beast or from the heavenly perspective which John’s visions open for his readers” (p. 90).

“The perspective of heaven must break into the earthbound delusion of the beast’s propaganda” (p. 91).

“There are clearly only two options: to conquer and inherit the eschatological promises, or to suffer the second death in the lake of fire (21:8)” (p. 92).

If Christians are to “resist the powerful allurements of Babylon, they [need] an alternative and greater attraction” (p. 129).

“God’s service is perfect freedom (cf. 1 Pet. 2:16). Because God’s will is the moral truth of our own being as his creatures, we shall find our fulfillment only when, through our free obedience, his will becomes also the spontaneous desire of our hearts” (p. 142-43).

“Only a purified vision of the transcendence of God… can effectively resist the human tendency to idolatry which consists in absolutizing aspects of this world. The worship of the true God is the power of resistance to the deification of military and political power (the beast) and economic prosperity (Babylon)” (p. 160).

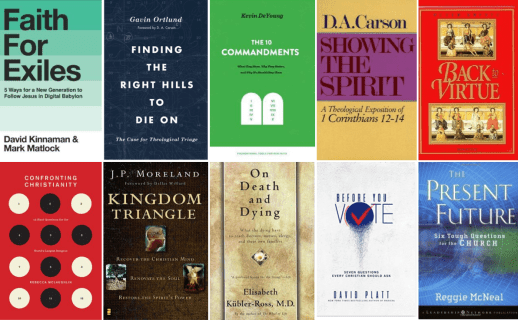

10 of the Books I Plan to Read in 2021

The Ten Best Books I Read in 2020

Here are my ten favorite books that I read in 2020 (they’re listed in alphabetical order by the author’s last name):

- D.A. Carson, Showing the Spirit: A Theological Exposition of 1 Corinthians 12–14

- Kevin DeYoung, The Ten Commandments: What They Mean, Why They Matter, and Why We Should Obey Them

- David Kinnaman, Faith for Exiles: Five Ways to Help Young Christians Be Resilient, Follow Jesus, and Live Differently in Digital Babylon

- Peter Kreeft, Back to Virtue: Traditional Moral Wisdom for Modern Moral Confusion

- Elisabeth Kübler-Ross, On Death and Dying

- Rebecca McLaughlin, Confronting Christianity: 12 Hard Questions for the World’s Largest Religion

- Reggie McNeal, The Present Future: Six Tough Questions for the Church

- J.P. Moreland, Kingdom Triangle: Recover the Christian Mind, Renovate the Soul, Restore the Spirit’s Power

- Gavin Ortlund, Finding the Right Hills to Die on: The Case for Theological Triage

- David Platt, Before You Vote: Seven Questions Every Christian Should Ask

And five runner-ups:

- Andy Crouch, Playing God: Redeeming the Gift of Power

- Albert Mohler Jr., The Gathering Storm: Secularism, Culture, and the Church

- Tony Reinke, Competing Spectacles: Treasuring Christ in the Media Age

- Deepak Reju, On Guard: Preventing and Responding to Child Abuse at Church

- Mark Dark Vroegop, Clouds, Deep Mercy: Discovering the Grace of Lament

Here are my favorite books from last year.

10 Ways to Read More Books in 2021

I read 70+ books in 2020.[1] Below I’ll tell you how.

“If you ain’t cheating, you ain’t trying.” I don’t think you should cheat. Cheating is wrong. But you should, however, make the most of every advantage you have as best as you can.

That’s what I seek to do with reading. I take advantage of everything I can.

I read all sorts of books for all sorts of reasons. Depending on the reason for reading and the type of book, I will read it in a different way. Some people shun audiobooks. But, I personally don’t get that. There are all sorts of reasons for reading and all sorts of ways that people retain things best.

As I said, I think we should wisely take advantage of everything we can as best as we personally can.[2]

Here are nine things I’ve used to my advantage:

1) Time

Time is the most precious commodity there is. Even little bits of gold have value, how much more small slots of time!

You can get a lot read when you make the most of small time slots. Waiting can easily turn into productive reading. I always have a book on hand. And my wife often listens to audiobooks while doing dishes or laundry.

2) Old fashioned books

Always have one with you. You never know when you’ll be able to get a few paragraphs or a few pages read.

3) Kindle app on my phone

It’s always with me. I always have a book I’m reading on Kindle.

4) Hoopla or Libby

Hoopla and Libby are free apps and one of them should be available through your local library. I’ve used them both at different times to listen to tons of books.

5) Audible

Audible is an audiobook service. My wife and I had a membership for a long time. It was great.

6) ChristianAudio

ChristianAudio is an audiobook service that provides Christian audiobooks. You can signup for a free audiobook a month.

7) Speechify

Speechify is an amazing app. It was created by Cliff Weitzman, someone with dyslexia, to help people with dyslexia.

With Speechify you can take a picture of a page in a book and it will convert it to audio. I will sometimes buy a book on Kindle and take a screenshot of each page of the Kindle book and load it on to Speechify. In this way, I can listen to the book.

I can also still make notes. If something sticks out to me that I want to capture I’ll take a screenshot on the Speechify app. Then I’ll search the keywords from the screenshot on the Kindle book and highlight and make any notes I want to make.

Speechify has been a huge blessing to me. I read very slowly but when I use Speechify I can read over 650 words per minute. Speechify probably triples my reading speed but I’m still able to retain what I read and make notes.

8) A community of book lovers

I have multiple friends (including my wife!) that love to talk books and encourage the reading of good books.

9) Goodreads

Goodreads is a social media site for reading. Goodreads allows you to track and review books you’ve read as well as receive recommendations from friends. You can see my Goodreads account here.

10) Pocket (very helpful but not for books)

Pocket is an app that allows you to save articles to your “pocket.” It’s a great way to save and organize articles. But, the thing I enjoy most is that it has a function that allows you to listen to articles.

Quotes from The Christian Faith by Michael Horton

“A mystery is inexhaustible, but a contradiction is nonsense. For example, to say that God is one in essence and three in persons is indeed a mystery, but it is not a contradiction. Believers revel in the paradox of the God who became flesh, but divine and human natures united in one person is not a contradiction. It is not reason that recoils before such miracles as ex nihilo creation, the exodus, or the virginal conception, atoning death, and bodily resurrection of Jesus Christ. Rather, it is the fallen heart of reasoners that refuses to entertain even the possibility of a world in which divine acts occur” (Michael Horton, The Christian Faith, 101).

“Faithful reasoning neither enthrones nor avoids human questioning. Rather, it presupposes a humble submission to the way things actually are, not the way we expect them to be. Faithful reasoning anticipates surprise, because it is genuinely open to reality. If reality is always exactly what we assumed, then the chances are good that we have enclosed ourselves in a safe cocoon of subjective assertions. Unbelief is its own form of fideism, a close-mindedness whose a priori, untested, and unproven commitments have already restricted the horizon of possible interpretations” (Horton, The Christian Faith, 102).

“Ethical imperatives are extrapolated from gospel indicatives. The gospel of free justification liberates us to embrace the very law that once condemned us” (Ibid., 640).

“In the Greek language we must differentiate between the indicative mood, which is declarative (simply describing a certain state of affairs), and the imperative mood, which sets forth commands). For example, in Romans Paul first explains who believers were in Adam and their new status in Christ (justification) and then reasons from this indicative to the imperatives as a logical conclusion: ‘Do not present your members to sin as instruments for unrighteousness, but present yourselves to God as those who have been brought from death to life…’ (Ro 6:13). He concludes with another imperative (command), but this time it is really an indicative: ‘For sin will have no dominion over you, since you are not under law but under grace’ (v.14)” (Ibid., 649).

“Where most people think that the goal of religion is to get people to become something that they are not, the Scriptures call believers to become more and more what they already are in Christ” (Ibid., 652).

“Although we cannot work for our own salvation, we can and must work out that salvation in all areas of our daily practice. When God calls, ‘Adam, where are you?’ the Spirit leads us to answer, ‘In Christ’ (Ibid., 662).

“It is crucial to remind ourselves that in this daily human act of turning, we are always turning not only from sin but toward Christ rather than toward our own experience or piety” (Ibid., 663).

10 Quotes from John Piper’s book, Future Grace

“The commandments of God are not negligible because we are under grace. They are double because we are under grace” (John Piper, Future Grace, 168).

“The way to fight sin in our lives is to battle our bent toward unbelief” (Piper, Future Grace, 219).

“The faith that justifies is a faith that also sanctifies… The test of whether our faith is the kind of faith that justifies is whether it is the kind of faith that sanctifies” (Ibid., 332).

“The blood of Christ obtained for us not only the cancellation of sin, but also the conquering of sin. This is the grace we live under—the sin-conquering, not just sin-canceling, grace of God (Ibid., 333).

“The problem with our love for happiness is never that its intensity is too great. The main problem is that it flows in the wrong channels toward the wrong objects, because our nature is corrupt and in desperate need of renovation by the Holy Spirit” (Ibid., 397).

“The role of Gods Word is to feed faith’s appetite for God. And, in doing this, it weans my heart away from the deceptive taste of lust” (Ibid., 335)

“It is this superior satisfaction in future grace that breaks the power of lust. With all eternity hanging in the balance, we fight the fight of faith. Our chief enemy is the lie that says sin will make our future happier. Our chief weapon is the Truth that says God will make our future happier. We must fight it with a massive promise of superior happiness. We must swallow up the little flicker of lust’s pleasure in the conflagration of holy satisfaction” (Ibid., 336).

“There are no closed countries to those who assume that persecution, imprisonment and death are the likely results of spreading the gospel. (Matthew 24:9. RSV)” (Ibid., 345).

“Perseverance in faith is, in one sense, the condition of justification; that is, the promise of acceptance is made only to a persevering sort of faith, and the proper evidence of it being that sort is its actual perseverance” (Piper, Future Grace, 26 quoting Jonathan Edwards).

“Humility follows God like a shadow” (Ibid., 85).

10 Quotes from Jonathan Pennington’s book, Jesus the Great Philosopher

I appreciated Pennington’s book. He did a good job showing that “Christianity is more than a religion. It is a deeply sophisticated philosophy” (Jonathan T. Pennington, Jesus the Great Philosopher: Rediscovering the Wisdom Needed for the Good Life, 159).

Here are 10 quotes that stuck out to me:

“When we try to live without knowledge of physics and metaphysics—how the would is and how works—then we are foolish, not wise, living randomly, haphazardly, without direction or hope for security, happiness, or peace” (Pennington, Jesus the Great Philosopher, p. 23).

“The Bible is addressing precisely the same questions as traditional philosophy” (p. 53).

“The Old and New Testaments teach people to act in certain ways, knowing that cognitive and volitional choices not only reflect our emotions but also affect and educate them” (p. 120-21).

“Without intentional reflection, we will live our lives without direction and purpose. Or worse, we will live with misdirected and distorted goals” (p. 124).

“Relationships aren’t an add-on to life, they make up our life” (p. 134).

“Jesus himself emphasized that his kingdom is not of this world (John 18:36). This does not mean Christians are free to ignore this world, but instead it frees Christians to relate in a gracious and humble way, knowing their citizenship is ultimately something more and greater and different” (p. 166-67).

“The reason Jesus was so infuriating to both religious and government leaders was not because he was taking up arms and trying to overthrow governments but because his radical teachings were so subversive to society. Jesus was subversive because he sought to reform all sorts of relationships. In his teachings and actions, Jesus continually subverted fundamental values of both Jewish and Greco-Roman society” (p. 172).

“Christianity is a deeply intentional and practical philosophy of relationships” (p. 173).

“Unlike sitcom relationships, the reality is that our lives are broken through sin—the brokenness not only of sin that has corrupted creation itself but also of personal acts of evil, foolishness, and harm. Thus, the Christian philosophy’s vision for relationships within God’s kingdom is not naive or idealistic” (p. 181).

Back to Virtue by Peter Kreeft

I recently read Peter Kreeft’s book Back to Virtue. Kreeft is a Roman Catholic philosopher, theologian, apologist, and a prolific author. He is a professor of philosophy at Boston College and The King’s College.

Here are some quotes from Back to Virtue that stuck out to me:

“We control nature, but we cannot or will not control ourselves. Self-control is ‘out’ exactly when nature control is ‘in’, that is, exactly when self-control is most needed” (Peter Kreeft, Back to Virtue, 23).

“Nothing is so surely and quickly dated as the up-to-date” (Peter Kreeft, Back to Virtue, 63).

“It is hard to be totally courageous without hope in Heaven. Why risk your life if there is no hope in Heaven. Why risk your life if there is no hope that your story ends in anything other than worms and decay” (Kreeft, Back to Virtue, 72).

“The only way to ‘the imitation of Christ’ is the incorporation into Christ” (Ibid., 84).

“There are only two kinds of people: fools, who think they are wise, and the wise, who know they are fools” (Ibid., 99).

“Humility is thinking less about yourself, not thinking less of yourself” (Ibid., 100).

“God has more power in one breath of his spirit than all the winds of war, all the nuclear bombs, all the energy of all the suns in all the galaxies, all the fury of Hell itself” (Ibid., 105).

“We can possess only what is less than ourselves, things, objects… We are possessed by what is greater than ourselves—God and his attributes, Truth, Goodness, Beauty. This alone can make us happy, can satisfy the restless heart, can fill the infinite, God-shaped hole at the center of our being” (Ibid., 112).

“The beatitude does not say merely: ‘Blessed are the peace-lovers,’ but something rarer: ‘Blessed are the peacemakers’” (Ibid., 146).

“There is only one thing that never gets boring: God… Modern man has… sorrow about God, because God is dead to him. He is the cosmic orphan. Nothing can take the place of his dead Father; all idols fail, and bore” (Ibid., 157).

“God’s single solution to all our problems is Jesus Christ” (Ibid., 172).

“An absolute being, an absolute motive, and an absolute hope can alone generate an absolute passion. God, love and Heaven are the three greatest sources of passion possible” (Ibid., 192).