Body and Spirit: Christianity and the Importance of Exercise

I recently read David Mathis’ book, A Little Theology of Exercise. It is good and reminded me to finish writing something I started in 2023…

I have been exercising religiously and consistently for the past five years or so.[1] I use both “religiously” and “consistently” purposely here. I don’t primarily exercise for aesthetics or athleticism. But because “exercise is of some value,” as the Apostle Paul says (1 Timothy 4:8).

Some of the values I have seen in my own life: mental clarity, more patience and less anger, self-discipline, less stress (and fewer stress-related canker sores), and less back and knee pain. But that’s not it. My exercise has been religious too.

Exercise can actually be a type of spiritual discipline and an act of worship when done for the right reasons. Christians need to reject lazy and sedentary lives while also avoiding obsession with fitness and body image. Exercise is to serve the higher purpose of loving God and others well.

Christians know the body is not evil or unimportant; it is a precious part of what it means to be human. So, our bodies are to be stewarded to God’s glory. By working to keep our bodies healthy, we position ourselves to better serve God and others.[2] Exercise can help us better steward our time on earth.

Jonathan Edwards, the 18th-century theologian and philosopher, saw the benefit of regular exercise, although he didn’t have a gym to go to. In the winter, when he couldn’t ride his horse and walk, he would “chop wood, moderately, for the space of half an hour or more.”[3] I don’t think what we do is as important as doing something. We all have things we gravitate towards. Physical activity is helpful for us.

John J. Ratey’s book, Spark: The Revolutionary New Science of Exercise and the Brain, was also helpful. He shows that exercise…

- helps with stress

- is especially helpful for those with ADHD

- is very beneficial for recovering addicts; it can assist the fight for sobriety because of how the reward system works in our brains

- helps with mental agility

- helps spur the growth of new brain cells

- helps combat anxiety and depression

- helps prevent and heal neurodegenerative disorders

Exercise is important. I love what the Apostle Paul says: “Physical training is good, but training for godliness is much better, promising benefits in this life and in the life to come” (1 Timothy 4:8). Of course, the Apostle Paul did not live a sedentary lifestyle.

Paul walked some 10,000 miles on his missionary journeys. So, Paul, although bookish, was also active. Jesus also did not live a sedentary lifestyle. Jesus was a carpenter/masonry craftsman, several of Jesus’ disciples were fishermen, and Paul was a tentmaker.

“Regular human movement has been assumed throughout history.” But now, as David Mathis said, “We have cars, and we walk far less. We have machines and other labor-saving devices, and so we use our hands less. We have screens, and we move less. Added to that, in our prosperity and decadence, food and (sugar-saturated) drinks are available to us like never before.”

We definitely need to hear “godliness is much better,” but I think we also need to hear, “physical training is good.” This is especially the case because we drive, we don’t walk. We order fish, we don’t hoist them in from a ship. We build more things on Minecraft than with our hands.

It does make sense that our spiritual lives are more important than our physical fitness. But I don’t believe there is some huge separation between the two. Activity helps activate our minds. And the Bible says we are supposed to love the Lord our God with all our heart, soul, mind, and strength, and we are to glorify God in whatever we do. The Bible also says that Christians are temples of the living God; that doesn’t mean that our bodies must be marble, but it does mean that we shouldn’t treat our bodies like latrines.

We are embodied beings, not disembodied souls. Our bodies, it is true, are not glorified yet; they are battered and broken, but they’re not inherently bad. So, let’s exercise for effectiveness and longevity, not self-worth or selfies. God is the one who instills our self-worth (and gave Jesus for us), and being obsessed with selfies is silly.

Notes

[1] Exercise has been a part of my life since about as long as I can remember. I started playing soccer when I was five and remember first being allowed to jog to Fleets Fitness when I was thirteen.

[2] Scripture says to do good to people as you have opportunity (Gal. 6:7), but more and more, if it is difficult to get off the couch, it will also be increasingly difficult to help people. So, I think disciplining ourselves for the sake of godliness (1 Timothy 4:7) can and even should include physical exercise.

[3] The Works of President Edwards.

*Photo by Mike Cox

Should Christians Legislate Morality?

Christians Should Not Enforce “Vertical” Morality

In our modern, pluralistic, and heavily secularized society, John Warwick Montgomery points out that Christians should be particularly cautious not to jeopardize the spread of the gospel by insensitively imposing Christian morality on unbelievers. We must avoid any recurrence of the Puritan Commonwealth, where people are compelled to act externally as Christians regardless of their true faith. Unfortunately, these efforts often lead to the institutionalization of hypocrisy and a decline in respect for genuine Christian values.[1] It can also lead people to a false assurance of a right relationship with God.

Instead, Montgomery says Christians should recognize that Scripture presents two distinct types of moral commands. We see this in the first and second parts of the Ten Commandments.[2] In the first part, we see duties related to God. These commands cover the relationship between individuals and God (“vertical” morality). In the second part, we see duties related to neighbors. These commands cover the relationship between individuals and other people (“horizontal” morality).

Montgomery believes it is crucial not to impose the first part of the Ten Commandments on unbelievers. These commands are:

- “You must not have any other god but Me.”

- “You must not make for yourself an idol.”

- “You must not misuse the name of the Lord your God.”

- “Remember to observe the Sabbath day by keeping it holy.”

Even if Christians are in the majority in a country, they should not impose laws related to the above four commandments. “This is because the proper relationship with God can only be established through voluntary, personal decision and commitment.”[3]

1 Corinthians 5:10 is an important verse for us to consider on this subject as well. Paul argues that avoiding all sinful individuals in the world would mean that Christians would need to “leave the world” entirely, which is an impractical and unrealistic standard. Instead, the church’s primary responsibility is not to judge those outside the faith; it is their duty to judge those who claim to be believers but live in sin within the church.

The Quran says there is no compulsion in religion. Jesus demonstrated that principle. He never forced anyone to follow Him. That’s what we see throughout the New Testament. Christians are to be evangelistic and strive to compel people to see the goodness and glory of Jesus. Still, they are never commanded to command people to bow to Jesus.

Christians Should Work Towards A General “Horizontal” Morality

Christians should, however, encourage people towards general “horizontal” morality. Even while the focus in the New Testament is on the morality of Jesus’ followers, we do see warrant for the promotion of social order and general morality. I think of John the Baptizer and the Apostle Paul, for example (Mark 6:14-20; Matt. 14:1-12; Acts 16:35-39; 24:25; 1 Tim. 2:1-4 also see Rom. 13 and 1 Peter 2). But the letters of the New Testament were written to Christians, telling Christians how to live.

Here’s the second part of the Ten Commandments, which are good for every society to lovingly and practically apply.

- “Honor your father and your mother”

- “You shall not murder”

- “You shall not commit adultery”

- “You shall not steal”

- “You shall not bear false witness against your neighbor”

- “You shall not covet”

These commands are applied in various ways throughout the Bible. For example, the Bible talks about the importance of railings on the top of buildings to protect people from falling off and getting hurt or killed.

But even here, we don’t want to put our hope or emphasis on “horizontal” morality. Part of the point of the law is to point us to our need for Jesus. It is not an end in itself. So, we must remember that mere morality is not the solution.

The Problem of Secularism and Morality

Britannica says secularism is “a worldview or political principle that separates religion from other realms of human existence, often putting greater emphasis on nonreligious aspects of human life or, more specifically, separating religion from the political realm.”

One of the problems with secularism, though, is that it is not set up very well to give us a societal analysis. How is secularism going to provide us with:

- The Ideal of what’s healthy

- Observation of symptoms

- Diagnosis or analysis of the disease/disorder

- Prognosis or prediction of cure/remedy

- Prescription or instruction for treatment/action for a cure

Secularists believe Christians should not legislate morality. They say that religion has no place in government. Christian beliefs are not allowed, but their core beliefs are allowed. But, as Britannica aludes to, secularism is really an ultimate commitment—a whole world-and-life-view.

Even atheism has the markings of a religion. Atheists have a creed. Theirs is just that there is no god. Atheism addresses the ultimate concerns of life and existence and answers the questions of who people are and what they should value. A committed atheist is even unlikely to marry someone outside of their beliefs. Many atheists even belong to a group and may even attend occasional meetings (see e.g., atheists.org) and have their own literature they read that supports their beliefs.

A merely secular society cannot give a moral framework that transcends individual belief systems. We are left with a “might makes right morality.” It seems to me that secularism leaves us with the column on the left, whereas Christianity gives us the column on the right.

I believe we need and should want Christianity to help our nation work towards a general “horizontal” morality. Our Founding Fathers (along with Alexis de Tocqueville), many of whom were deists and not Christians, agree. Yet, Christians should realize that legislating morality is not the answer.

Legislating Morality is Not the Ultimate Solution

Christians both understand that sinners will sin and that morality is good for the nation. Righteousness exalts the land, as Proverbs says (Prov. 14:34). Yet, Christians are compassionate and humble. We realize that we all stumble in many ways, as the letter of James says, but if we can help people from stumbling, that’s good. But Christians don’t confuse the kingdom of man with the Kingdom of God. Christians know that here we have no lasting city, but we seek the City that is to come (Heb. 13:14).

Legislating morality is not the solution; Jesus is. As C.H. Spurgeon said, “Nothing but the Gospel can sweep away social evil… The Gospel is the great broom with which to cleanse the filthiness of the city; nothing else will avail.”

Paul David Tripp has wisely said that “We should be thankful for the wisdom of God’s law, but we should also be careful not to ask it to do what only grace can accomplish.” It is the Spirit of God that transforms, although it is true that He often works through law. We need our rocky hearts to become flesh through the work of the Spirit.

Conclusion

The question of whether Christians should legislate morality reveals the complexities of faith in a diverse and secular society. While Christians are called to embody and promote a morality rooted in their faith, imposing a “vertical” morality can hinder the spread of the gospel, foster hypocrisy, and promote a misunderstanding of genuine faith. Instead, the focus should be on humbly and lovingly encouraging “horizontal” morality—principles that promote societal well-being and can be embraced by individuals regardless of their faith.

As apprentices of Jesus, Christians are primarily called to lead by example and encourage ethical behavior rooted in love and respect for one another. The emphasis should be on exemplifying Jesus’ teachings and fostering relationships that draw others to the faith, rather than seeking to enforce morality. That’s what Jesus Himself did.

By fostering relationships and demonstrating the transformative love of Jesus, Christians can influence the moral fabric of society without simply relying on legislation. True change comes through the work of the Holy Spirit rather than external mandates. In this way, the Christian community can contribute to a more just and moral society while remaining faithful to the fundamental teachings of their faith.

Notes

[1] John Warwick Montgomery,Theology: Good, Bad, and Mysterious, 122.

[2] Often referred to as the First and Second Tables of the Decalogue. The “First Table” consists of commands 1-4 and has to do with people’s relationship with God (vertical relationship). The “Second Table” consists of commands 5-10 and has to do with people’s relationship with other humans (horizontal relationships). The First Table can be summed up by “love God,” and the Second Table can be summed up by “love others.”

[3] Montgomery, Theology: Good, Bad, and Mysterious, 123.

Revelation Is Not Mainly About When the World Will End

Eschatology is not mainly about predicting the end, but about living rightly in light of the end. Revelation does not reveal when exactly the world will end, but it does reveal what the end will entail and whose side we want to be on. As many commentators note, the visions in Revelation primarily confront us with God’s demands and promises, they are not meant to satisfy our curiosity about minute end-time details.[1] Vern Poythress says it this way: “Revelation renews us, not so much from particular instructions about particular future events, but from showing us God, who will bring to pass all events in his own time and his own way.”[2]

Interestingly, “one in four Americans believe that the world will end within his or her lifetime.”[3] But America should never be the interpretive lens by which we interpret and think about eschatology. As Craig S. Keener has said,

If today’s newspapers are a necessary key to interpreting the book, then no generation until our own could have understood and obeyed the book… They could not have read the book as Scripture profitable for teaching and correction—an approach that does not fit a high view of biblical authority (cf. 2 Tim. 3:16-17).[4]

There have been many specific failed predictions. Actually, “The failure rate for apocalyptic predictions sits right at 100 percent.”[5] Sadly, sometimes what we think is in the Bible “is actually an indicator of our own biases and pre-conceptions.”[6] Hal Lindsey predicted the end in 2000. Many believe Y2K would be the end. Harold Camping said the rapture would happen on September 6th, 1994. His radio “station raised millions to get word of the end on billboards, pamphlets, and the radio.”[7] One newspaper “estimated that worldwide more than $100 million was spent by Family Radio on promotion of the date.”[8] For some who had “pinned their beliefs to this date, the failure of Camping’s apocalypse left them lost, with little trust in God.” They were “disappointed and adrift” and for some “there was financial ruin.”[9] That’s sad and unnecessary.

As we study eschatology, we should do so with the world and the scope of history in mind. Remembering intense tribulation has

been present at various times, with great severity and over large areas. We think especially of the Mohammedan invasion in the seventh and eighth centuries which swept across all of the Near East, up into Europe as far as Italy and Austria, across all of North Africa, across Spain and into France. The Black Plague ravaged Asia and Europe in the fourteenth century. The Thirty Years War devastated much of central Europe in the seventeenth century. There have been two so-called World Wars in our twentieth century. For a time each of those seemed to qualify as great tribulation.[10]

Also, “As for the Antichrist, various ones have been temporarily cast in that role: Attila the Hun in the fifth century; the pope at the time of the Protestant Reformation; Napoleon in the nineteenth century; Mussolini, Hitler and Stalin in the twentieth century.”[11]

As faithful Christians, we should do our best to present ourselves to God as approved, workers who have no need to be ashamed, rightly handling the word of truth” (2 Tim. 2:15). We should know the “signs of the times”[12] and we must be faithful and ready for the return of Jesus. But, “because the exact time when Christ will return is not known, the church must live with a sense of urgency, realizing that the end of history may be very near. At the same time, however, the church must continue to plan and work for a future on this present earth which may still last a long time.”[13]

Notes

[1] Craig S. Keener, The NIV Application Commentary: Revelation, 32. Since Revelation is both apocalyptic and prophecy we must understand that its primary purpose is to provide words of comfort and challenge to God’s people then and now, rather than precisly predicting the future, especially in great detail. Visions of the future are not an end in themselves but rather a means by which people are to be warned and to comforted (Michael J. Gorman, Reading Revelation Responsibly: Uncivil Worship and Witness: Followingthe Lamb into the New Creation, 41).

[2] Vern Poythress, The Returning King: A Guide to the Book of Revelation.

[3] Jessica Tinklenberg Devega, Guesses, Goofs, and Prophetic Failures, 10.

[4] Keener, The NIV Application Commentary: Revelation, 30.

[5] Devega, Guesses, Goofs, and Prophetic Failures, 193.

[6] Ibid., 7.

[7] Ibid., 157.

[8] Ibid., 159.

[9] Ibid., 161.

[10] Loraine Boettner, “A Postmillennial Response” in The Meaning of the Millennium, 204-05.

[11] Boettner, “A Postmillennial Response,” 205.

[12] Wars, famines, earthquakes, tribulation, apostasy, antichrist(s), the proclamation of the gospel to the nations, and the salvation of the fullness of Israel.

[13] Anthony A. Hoekema, “Amillennialism” in The Meaning of the Millennium, 178-79.

We Miss our Way in So Many Ways

I appreciate this quote from Richard Lovelace: “The goal of authentic spirituality is a life which escapes from the closed circle of spiritual self-indulgence, or even self-improvement, to become absorbed in the love of God and other persons.”[1]

We miss our way in so many ways. Even our spirituality and self-improvement can be directed to the wrong ends and by the wrong means.

When our attention rests primarily on self, instead of Jesus our Savior, innumerable problems result. Notice the Apostle Paul said, “Him [Jesus] we proclaim… that we may present everyone mature in Christ” (Col. 1:28). It is when our mind, heart, affection, and will are drawn to Jesus that we are more and more transformed into His image.

closed circle of spiritual self-indulgence or self-improvement

Like a Pharisee, we can be so obsessed with ourselves that we miss God and the precious people made in His image.

In Greek mythology, Narcissus was a handsome young man who fell in love with his own reflection. Narcissus drowned while gazing at his own reflection in the water. We, too, can be dangerously focused on ourselves.

“Authentic spirituality,” as Lovelace says, escapes the clutches of such navel-gazing to the ideal that God always intended. That is, to be “absorbed in the love of God and other persons.”

absorbed in the love of God and other persons

Jesus made it so simple. We need simple. Love God. Radically love God with every ounce of your being—heart, soul, mind, and strength. And love others.

“The substance of real spirituality is love. It is not our love but God’s that moves into our consciousness, warmly affirming that he values and cares for us with infinite concern. But his love also sweeps us away from self-preoccupation into a delight in his unlimited beauty and transcendent glory. It moves us to obey him and leads us to cherish the gifts and graces of others.”[2]

Augustine said, “Love God and do whatever you please: for the soul trained in love to God will do nothing to offend the One who is Beloved.” The gravitational pull of the love of God transforms us.

Notes

[1] Richard F. Lovelace, Renewal As a Way of Life: A Guidebook for Spiritual Growth, 18.

[2] Ibid.

What sets Christianity apart? (part 3)

In Part One, we examined the commonalities among world religions and inquired whether they are fundamentally the same. We discovered that they’re not, and we examined two aspects that distinguish Christianity. In Part Two, we discussed four distinct aspects of Christianity that distinguish it from other religions. Here, we will finish by considering four aspects that set Christianity apart.

7. Positive World Impact

Jesus, a backwater country craftsman, has had an undisputed impact on history and the world. Stephen Prothero has said, “There is no disputing the influence Jesus has had on world history. The Library of Congress in Washington, DC, holds more books about Jesus (roughly seventeen thousand) than about any other historical figure—twice as many as the runner-up, Shakespeare. Worldwide, there are an estimated 187,000 books about Jesus in five hundred different languages.’ Jesus even has a country named after him: the Central American nation of El Salvador (“The Savior”).”[1]

Some people would dispute whether Jesus’ impact has been positive. But religion is generally seen as having a positive impact on humanity. This has been statistically demonstrated. That, however, is not to say religion hasn’t also had a negative impact in certain circumstances. We can quickly cite the Crusades and the September 11th attacks to prove that religion is not always applied in a good way. But, generally, religion is a net positive.[2]

Christianity is specifically good for humanity. This is true statistically and historically, which makes sense because I believe Christianity is true factually. Think of the impact Christianity has had on hospitals. Think of the names of hospitals you know of; most of their names are probably Christian. If not, even still, most of them have Christian histories. But it’s not just hospitals. Consider the sanctity of human life, the value of women, health care, education, science, the abolition of slavery, music, literature, art, and charities.[3] For more on this, I encourage you to check out How Christianity Changed the World by Alvin J. Schmidt, Dominion: How the Christian Revolution Remade the World by Tom Holland, or several books by Rodney Stark.

Christopher Watkin even says that “the reason Jesus’s teaching does not take our breath away is that it has so completely transformed how we think and act already. As Tom Holland reminds us, it is only the incomplete revolutions that are remembered; those that triumph are simply taken for granted. The revolution brought about by Jesus’s teaching and life has triumphed so completely that, religious and secular alike, we take it for granted today.”[4] So, I believe Christianity had a uniquely positive impact on the world.

8. Salvation by Grace

Muslims believe there is salvation through submission. That is, if you confess and carry out the pillars of Islam, you may obtain salvation. Christians believe that “if you confess with your mouth that Jesus is Lord and believe in your heart that God raised Him from the dead, you will be saved” (Rom. 10:9). Christianity is unique because it teaches that salvation is by grace.

This is how Micah 7:18-19 says it: “Who is a God like You, who pardons sin and forgives the transgression of the remnant of His inheritance? You do not stay angry forever but delight to show mercy. You will again have compassion on us; You will tread our sins underfoot and hurl all our iniquities into the depths of the sea.”

Salvation is by grace through faith. Here’s how Ephesians 2:8-10 says it, “For by grace you have been saved through faith. And this is not your own doing; it is the gift of God, not a result of works, so that no one may boast. For we are his workmanship, created in Christ Jesus for good works, which God prepared beforehand, that we should walk in them.”

It should be understood that “faith works.” It does not stay stagnant. As Ephesians 2 says, Christians believe salvation comes through God’s grace as a gift, but that doesn’t lead to license to do whatever. It leads to a life filled with good works.

9. Exclusivity, Inclusivity, and Equality

Christianity is at the same time the most exclusive and inclusive religion. Christianity says that Jesus alone is the way, the truth, the life, and no one gets to God the Father except through Him (Jn. 14:6); and it says whosoever believes—red, black, white, rich, poor, whoever from wherever—will have eternal life.

So, on the exclusive side, Christians believe what 1 Timothy 2:5 says, that “there is one God, and there is one mediator between God and men, the man Christ Jesus.” So, there is one way of salvation—Messiah Jesus. Yet, 1 Timothy 2:6 shows us how inclusive Christianity is. It says Jesus “gave Himself as a ransom for all.” There are no ethnic or cultural requirements.

Christianity is the most global religion. It has the largest number of adherents worldwide. Christianity is followed closely in size by Islam. But I am not making the ad populum argument here. Just because more people say they’re Christian doesn’t make Christianity true.[5] My point, rather, is that not only is Christianity the biggest religion, it is also the most culturally diverse. Muslims are more monolithic. Though that is not to say they are monolithic.[6] Take, for example, the Christian and Muslim religious texts. Islam’s scripture is only considered Allah’s word in Arabic.[7] Christianity seeks to translate the scripture into the languages of every people, tribe, language, nation, and tongue.

Prothero says Muslims “have always insisted that the Quran is revelation only in the original Arabic, Christians do not confine God’s speech to the Hebrew of their Old Testament or the Greek of their New Testament. In fact, while Muslims have resisted translating the Quran (the first English translation by a Muslim did not appear until the twentieth century), Christians have long viewed the translation, publication, and distribution of Bibles in assorted vernaculars as a sacred duty.”[8]

The Christian movement was diverse from the very beginning, ethnically and also socioeconomically (See e.g., Col. 3:11; Gal. 3:28). Christianity is the most ethnically dispersed religion, and Hinduism is the least dispersed.[9] Part of the reason Hinduism especially lacks diversity is because of its caste system. Even while India as a country no longer officially endorses the caste system, its effects are felt.

In contrast, Timothy Keller explains that the cross of Jesus should remove the pride and self-aggrandizement that lead to racial animosity and human disunity.[10] The Bible “insists on the equal value and dignity of all humans. The first churches united high and low classes, rich and poor, slaves and masters, and people of different racial backgrounds in uncomfortable, boundary-crushing fellowship.”[11]

Many may contend here that Christianity is unfair or bad because it says that Jesus is the only way. I’ve dealt with that objection elsewhere. But the fact that someone doesn’t like something does not make that thing untrue. We don’t have to like the truth for it to be true. “Comfort is important when it comes to furniture and headphones, but it is irrelevant when it comes to truth.”[12]

Others may object, if Christianity is the exclusively correct religion, then why are there so many world religions? Because we have a sensus divinitatis, or sense of the divine. This is for various reasons. For one, what can be known about God is plain to see, because God has shown it. “For His invisible attributes, namely, His eternal power and divine nature, have been clearly perceived, ever since the creation of the world, in the things that have been made” (Rom. 1:19-20). Second, Scripture also teaches and many people attest to having a conscience or the “law written on their hearts” (see Romans 2). Third, people have a sense of the divine because there is a spiritual realm. Most people throughout the globe and throughout history have believed in the spiritual realm. It is chronological and geographical snobbery to assume that we modern Westerners automatically know better.

So, the exclusivity of Jesus does not prove Christianity wrong. Although it may prove unpopular. It does make Christianity distinct from some other religions. Buddhism, Hinduism, and other religions hold that there are many ways of salvation (although “salvation” may not always be the best term).

Related to inclusivity and exclusivity is Christianity’s view of equality. The Bible teaches the equality of all humans by saying all humans are made in the image of God (Gen. 1:26-27). It also explains that we are all equally fallen. That is, we all sin and do wrong things. Lastly, it says that salvation is freely offered to all through Jesus.[13] In a similar way, the Bible shows the worth of women repeatedly, while the Qoran, for instance, is often disparaging of women, many believe, even allowing for abuse.

Naturalism, the belief that no God exists, gives no explanation or reason for equality. People who don’t believe in God or the relevance of God might believe in equality, but their belief is not based on any foundation. The idea of equality is accepted as true without proof or solid reason to believe it.

10. Relationship with God

Christians believe that we can have a relationship with God. This is different from Hinduism, for example. Most Hindus believe that the whole of the universe is itself divine. And most Buddhists don’t believe in a divine being. Folk, polytheistic, and animistic religions mainly seek to pacify the gods. “Islam diagnoses the world with ignorance and offers the remedy of sharia, a law to follow. Christianity diagnoses the world with brokenness and offers the remedy of God himself, a relationship with him that leads to heart transformation.”[14]

As we saw in Part One, Christianity teaches that God is an eternally relational being. God walked with Adam and Eve in the Garden in the beginning, He called Abraham to be His own, and He dwelt in the midst of His chosen people. God, in the form of Jesus, became flesh and lived among His people. Jesus taught His people to talk to God as Father. And we were even told that God dwells in us by His Spirit.

God is immensely relational. And God goes to great lengths so that His people can be with Him. In fact, the Christian scriptures say that God’s people will live with Him forever.

Conclusion

Christianity is unique among religions due to its Trinitarian Monotheism, belief in Jesus the Messiah who is the incarnate Son of God, and emphasis on His death and resurrection for humanity’s salvation. Christianity is both exclusive and inclusive, teaching that salvation is through Jesus Christ alone but available to all who believe. It offers a personal relationship with God, teaches salvation by grace through faith, and highlights human equality.

Notes

[1] Stephen Prothero, God Is Not One: The Eight Rival Religions that Run the World—and Why their Differences Matter, 70-71.

[2] “Religion is one of the greatest forces for evil in world history. Yet religion is also one of the greatest forces for good. Religions have put God’s stamp of approval on all sorts of demonic schemes, but religions also possess the power to say no to evil and banality” (Prothero, God Is Not One, 9).

[3] “By far the largest faith-based charity, according to the study, is Lutheran Services of America, with an annual operating revenue of about $21 billion. The study counted 17 more faith-based charities, all among Forbes’s 50 biggestcharities in America, with revenues ranging from $300 million (Cross International) to $6.6 billion (YMCA USA).Almost all the charities are Christian, except for the American Jewish Joint Distribution Committee, with an annual operating revenue of $400 million” (Julie Zauzmer, “Study: Religion contributes more to the U.S. economy than Facebook, Google and Apple combined” [September 15, 2016]).

[4] Christopher Watkin, Biblical Critical Theory: How the Bible’s Unfolding Story Makes Sense of Modern Life and Culture, 372.

[5] It doesn’t even make those people who say they’re Christian acturally Christians.

[6] Islam has many expressions. It is not monolithic. We are wrong if we think we understand Muslims because we have met one or read the Qur’an. That is a simplistic and false understanding. “Islam is a dynamic and varied religious tradition” (James D. Chancellor, “Islam and Violence,” in SBTS, 42.). In the same way, if you have met a Christian and read the New Testament, for example, that does not mean that you understand Christianity. “The range of contemporary Muslim religiosity varies tremendously. One of the reasons for this is that people understand and ‘use’ religion in a variety of ways; that is true whether we are dealing with Islam or Christianity or any other religion.” (Andrew Rippin, Muslims: Their Religious Beliefs and Practices (New York: Routledge, 2012), 311.)

[7] “Today the Quran is, of course, a book. But only about 20 percent of the world’s Muslims are able to read its Arabic, and even for them the Quran is, like the Vedas to Hindus, more about sound than about meaning” (Prothero, God Is Not One, 41).

[8] Prothero, God Is Not One, 67.

[9] See “The Global Religious Landscape,” Pew Research Center, December 18, 2012, http://www.pewforum.org/2012/12/18/global-religious-landscape-exec/.

[10] Timothy Keller, “The Bible and Race” https://quarterly.gospelinlife.com/the-bible-and-race/

[11] Rebecca McLaughlin, Confronting Christianity.

[12] Douglas Groothuis, Christian Apologetics: A Comprehensive Case for Biblical Faith, 137.

[13] See Christopher Watkin, 𝐵𝑖𝑏𝑙𝑖𝑐𝑎𝑙 𝐶𝑟𝑖𝑡𝑖𝑐𝑎𝑙 𝑇ℎ𝑒𝑜𝑟𝑦, 116.

[14] Prothero, No God But One, 45.

* Photo by Willian Justen de Vasconcellos

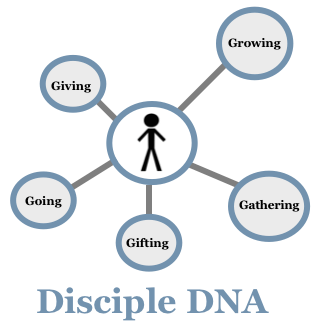

What’s Keeping Churches from Making Disciples?

Most churches know that discipleship is the main mission of the church. It’s in most mission statements. Yet, what kind of person does the church produce? The Christ-commanded product is a disciple who makes disciples.[1] “But for many churches, discipleship ranks toward the bottom of their priorities.”

Disciples trust Jesus as Lord and Boss, and follow Him by imitating His life and obeying His teachings.[2] Jesus calls disciples to deny themselves, take up their cross daily, and follow Him. This means disciples have repented of sin, forsaken the world, and committed their lives to follow Him. Historically, being a disciple involved learning, studying, and passing along the master’s teachings.[3]

Is this what the church is making? Many would say no. To a great extent, I agree. Even back in 1988, Bill Hull said,

The evangelical church has become weak, flabby, and too dependent on artificial means that can only simulate real spiritual power. Churches are too little like training centers to shape up the saints and too much like cardiopulmonary wards at the local hospital. We have proliferated self-indulgent consumer religion, the what-can-the-church-do-for-me syndrome. We are too easily satisfied with conventional success: bodies, bucks, and buildings. The average Christian resides in the comfort zone of “I pay the pastor to preach, administrate, and counsel. I pay him, he ministers to me… I am the consumer, he is the retailer.”[4]

While churches are biblically mandated and should be structured to make disciples, many churches prioritize attendance and attractive programs over discipleship, which results in discipleship deficiencies. Discipleship involves more than mere head knowledge; it involves intentionally instructing Jesus’ followers to “observe all that Jesus commanded” and to become disciple-makers themselves.

So, Hull says, “The crisis at the heart of the church is that we give disciple-making lip service, but do not practice it.”[5] If that’s the case, what are some of the issues keeping churches from making disciples?

1. Cultural Values

The cultural air that we breathe has an imperceptible impact. Christian Smith does a good job explaining some of the cultural values that we can easily unknowingly imbibe in his book, Why Religion Went Obsolete.

David Foster Wallace once told this story:

There are these two young fish swimming along, and they happen to meet an older fish swimming the other way. The older fish nods at them: “Morning, boys, how’s the water?” The two young fish swim on for a bit, and then one of them looks over at the other. “What the heck is water?”

It can be very difficult to be aware of our own culture and the impact that it is having on us.[6]

Our culture of consumerism and materialism is a big factor. So, Soong-Chan Rah, for example, has said,

Market-driven church that appeals to the materialistic desires of the individual consumer has resulted in a comfortable church, but not a biblical church. The church’s captivity to materialism has resulted in the unwillingness to confront sins such as economic and racial injustice and has produced consumers of religion rather than followers of Jesus.[7]

My point here is that our culture, even our church culture, does not place high value on discipleship. Although we may say we do. Our actions, or inaction, speak louder than our words.

We must let the Bible dictate our church culture, not culture.

2. Budgetary and Building Needs

Related to number one above, we have a church culture in America that is very dependent on buildings and budgets. We often think that for the church to continue, it has to “pack the pews” so the doors can stay open and the lights can stay on. Thus, the budgetary concerns can easily take precedence over all other concerns.

Here’s our thinking: What good can the church do if the church closes? Sunday comes quickly, and we need to have good sermons and programs if we hope to bring in the tithe or at least some form of giving.

Discipleship can easily take a back seat. Discipleship can be slow. Jesus walked, talked, and trained His disciples. This took time. Lots of time. Actual years. Yet, a movement of multiplication can happen when we make disciples.

We have conditioned ourselves for a type of fast-food or industrial revolution discipleship mentality. We want disciples quick, right off the express line. But that’s not how disciples have ever been made. But perhaps, especially now in our increasingly post-Christian, Bible-illiterate world.

We must care more about building up the actual body of Christ and not prioritize the church building (and budget).

3. Pastoral Identity Issues

Sadly, having been in pastoral ministry for 17 years and worked in various church contexts, sometimes there are pastoral identity issues that prevent pastors from investing in discipleship. It doesn’t feed a pastor’s ego if a lot of people don’t show up (however, “a lot of people” is defined). But Jesus didn’t always have a lot of people around Him. And sometimes when He did, He would say some very controversial things, and then many would leave. Christ’s goal was not a crowd, but “little Christs.”

A pastor’s ego is not fed when he equips others to do the work of the ministry, when he gives away ministry, helps others faithfully lead, shrugs out of the limelight, and pushes others towards success. But Christian ministry was never supposed to be about anyone’s ego.

But you know what is fed when a pastor doesn’t feed his ego? The church is fed, and it thus grows in both size and maturity because it is functioning as Jesus always intended it to function. Not as a one-person show, but as the church body being loving light wheresoever the church body finds itself throughout the week.

The church is an immaterial reality, and it was never meant to be bound by a material building; it was always meant to find physical expression in the living and breathing, walking and talking (incarnate), temples of God that Jesus’ people are. Just as the word of God was not bound, although Paul was bound in prison, God’s church is not bound to a building.

It is most healthy when it’s out loving in the wild world. That’s what it was always meant for. The telos or purpose of a candle is to be a source of light in darkness. It’s the same with the church. The church is called to be light in darkness and salt in a world of rot and decay. Notice, Jesus did not give the church something aspirational when He said, “You are the light of the world.” Jesus said something ontological. He said what we are.

I’m concerned that many pastors’ call to serve the church is self-serving. Pastors are often concerned about “their” church, not the Church. Pastors, sad to say, can be more concerned about their building being full rather than heaven being full.

The church is to make much of Jesus the Good Shepherd and not exalt any human.

4. Lack of Leadership Diversity (APEST)

“APEST” stands for apostles, prophets, evangelists, shepherds, and teachers. The Lord of the church has given these varied gifts to the church so that it will be balanced and mature (see Ephesians 4). Sadly, however, these gifts often find expression disconnected from the other gifts.

(It’s important to note that when I talk about APEST, I am talking about gifting. Not office or authority.)

Churches with certain types of leaders will move in certain directions. Teacher types tend to be thinkers, writers, researchers, and theologians. Shepherds tend to be carers, counselors, and community builders. Evangelists tend to be recruiters to the cause, apologists, and networkers. Prophets tend to call people to change, have holy criticism, and care deeply about social issues. Apostles pioneer, innovate, and create new approaches and structures.[8]

It seems the most common type of church, at least in the West, is the shepherd/teacher church.[9] This often results in a “knowledge-based community where right doctrine is seen to be more important than rightdoing.”[10] There is often an overemphasis on the sermon and Sunday service, and community, discipleship, and evangelism are an afterthought.

Again, diversity and balance are important. “The one-dimensional teaching church attracts people who love to be taught and tends to alienate other forms of spiritual expression. This is seldom a good thing because such churches simply become vulnerable to groupthink or even mass delusion. This has happened way too often… witness the many one-dimensional charismatic/vertical prophetic movements of the last century. Or consider the asymmetrical mega-church that markets religion and ends up producing consumptive, dependent, underdeveloped, cultural Christians with an exaggerated sense of entitlement.”[11]

The fact that “we have sought to negotiate our way in the world without three of the five functions (by elevating teaching and shepherding and neglecting evangelism, the prophetic, and the apostolic) accounts for so many of the problems we face in the church.”[12]

5. Lack of Commitment to the New Testament Ideal

Many times, we don’t know what we’re aiming for when it comes to disciples. We often lack a clear definition, or it’s a knowledge-based definition. Churches often emphasize orthodoxy (right belief) over orthopraxy (right practice). This results in many churchgoers who know a lot but don’t necessarily do a lot. But the great commission doesn’t just say “teach.” Its aim is practice. The Great Commission says, “teach them to observe everything I have commanded” (Matt. 28:20).

The church body is made up of individual members who together and separately worship, reflect, and share. The church is not an institution or an event. It is a living and moving organism. It is embodied all over every sector of society. So, we must ask, are disciples being made who make disciples who know, grow, and go?

The New Testament ideal is every believer practicing the missional mandate. It’s not just about knowing, but about going and doing all that Jesus commanded. The church must have growth goals or metrics that match the mission that Jesus has given to the church.

6. Lack of A Model to Emulate

The Apostle Paul said, “Imitate me as I imitate Christ” (1 Cor. 11:1). Jesus is the New Testament ideal. We are to imitate Him. And “Jesus poured His life into a few disciples and taught them to make other disciples.”[13]

So, we have an example to emulate in Jesus and Paul. Christian leaders must also provide examples and practice what they preach.[14] If pastors, for example, are—intentionally or unintentionally—held up as the Christian ideal, there are certain implications. If pastors mainly study and teach publicly or mainly function as CEOs, then that’s what is being modeled to people. And not lived everyday discipleship.

Conclusion

Good things often distract from the best things. And actually, some of the things churches do that they think are good only serve to create a culture of consumerism. Things must change. We must obey Jesus and make disciples who make disciples. We must make whatever structural and organizational changes are necessary to ensure we’re carrying out Jesus’ commission.[15]

I propose a new approach to “doing church” because, to a great extent, the way we’re currently doing church, at least in the West, is not working. We are not making disciples who make disciples in accordance with our Lord’s command. To a great extent, the church is making sitters. We must take our Boss’s words seriously and make structural and organizational changes.

Transformation happens less by argument and more by creating new rhythms and practices that shift not only people’s thinking but also their values and core commitments. We think, practice, and love our way into transformation. As Alan Hirsch has perceptively said, “The best way of making ideas have impact is to embed them into the very rhythms and habits of the community in the form of common tools and practices.”[16]

We need to stop just talking about discipleship and having programs for discipleship. We need something more radical. We need to scrap the old ways that allow for abstraction, and instead create regular rhythms that embody application.

Notes

[1] See Bill Hull, The Disciple-Making Pastor, 14.

[2] See Michael S. Heiser, What Does God Want? (Blind Spot Press, 2018), 94–95 and Ken Wilson, Finding God in the Bible: A Beginner’s Guide to Knowing God (Chicago: Moody Publishers, 2005), 86.

[3] Robert B. Sloan Jr., “Disciple,” in Holman Illustrated Bible Dictionary, ed. Chad Brand et al. (Nashville, TN: Holman Bible Publishers, 2003), 425.

[4] Bill Hull, The Disciple-Making Pastor, 12.

[5] Hull, The Disciple-Making Pastor, 15.

[6] Alan Hirsch, 5Q: Reactivating the Original Intelligence and Capacity of the Body of Christ.

[7] Soong-Chan Rah, The Next Evangelicalism, 63.

[8] There are a few Johns who stick out as teachers. John Calvin, Jonathan Edwards, and John MacArthur. Here are some other examples: George Whitefield (evangelist/apostle), John Piper (teacher/prophet), Charles Spurgeon (evangelist/prophet), Mother Teresa (shepherd) Richard Baxter (shepherd/teacher), Teresa of Avila (prophet/teacher), St. Patrick (apostle/shepherd) John Wimber (apostle/evangelist), David Platt (teacher/prophet), Hudson Taylor (apostle/evangelist), Catherine Booth (apostle), Dietrich Bonhoeffer (prophet/teacher), Billy Graham (evangelist), and Martin Luther King Jr. (prophet).

[9] “The church is actually perfectly designed by shepherds and teachers to produce shepherding and teaching outcomes. The organizational bias of the inherited form of church organization is in a real sense a reflection of the consciousness of the people who designed it in the first place!” (Alan Hirsch, 5Q).

[10] Hirsch, 5Q.

[11] Ibid.

[12] Ibid.

[13] Spader, Four Chair Discipling, 36. “These few disciples, within two years after the Spirit was poured out at Pentecost, went out and “filled Jerusalem” with Jesus’ teaching (Acts 5:28). Within four and a half years they had planted multiplying churches and equipped multiplying disciples (Acts 9:31). Within eighteen years it was said of them that they “turned the world upside down” (Acts 17;6 ESV). And in twenty-eight years it was said that the gospel is bearing fruit and growing throughout the whole world” (Col. 1:6). For four years Jesus lived out the values He championed in His Everyday Commission. He made disciples who could make disciples!” (Ibid.).

[14] Jesus had a specific method which we would be wise to observe and follow. See, for example, Matthew 9:35-39: “Jesus went throughout all the cities and villages, teaching in their synagogues and proclaiming the gospel of the kingdom and healing every disease and every affliction. When he saw the crowds, he had compassion for them, because they were harassed and helpless, like sheep without a shepherd. Then he said to his disciples, ‘The harvest is plentiful, but the laborers are few; therefore pray earnestly to the Lord of the harvest to send out laborers into his harvest.'” Jesus went, taught, proclaimed, healed, saw, and had compassion. He equipped disciples and sent them out into the harvest. He didn’t want them to sit in a building or do ministry in a building. What’s needed and what Jesus told us to pray for is laborers sent into the harvest.

[15] “Not much will change until we raise the issue and create controversy, until the American church is challenged to take the Great Commission seriously” (Hull, The Disciple-Making Pastor, 15).

[16] Hirsch, 5Q.

*Photo by Nellie Adamyan

What sets Christianity apart? (part 2)

In Part One, we found that part of what sets Christianity apart is trinitarian monotheism and God’s eternal love. Here we will add four more aspects that set Christianity apart from other religions.

3. The Incarnation of God

Christians believe that God loves the world so much that Jesus took on flesh and became man to die for the sins of the world (Jn. 1:1-3, 14, 29; 3:16). Other religions, such as Greek mythology, believe in gods who appeared in human form for various reasons, including love or punishment.[1] Greek gods, however, only temporarily took on human form. Jesus permanently became human.[2]

In Hinduism, the incarnation of a deity usually refers to Vishnu, who is said to have appeared in various avatars (e.g., Rama, Krishna, Narasimha, and Varaha). Other than Hinduism and various mythologies (which most people no longer take seriously), the concept of the incarnation of God is uncommon. However, Wikipedia does give a list of other people who have been considered deities. Egyptian pharaohs were considered deities, and North Korea’s Supreme Leader is considered a deity, for example. Interestingly, even on Wikipedia, Jesus is in a class of His own. He is listed by Himself under the “Controversial Deification” heading.

The Hindu avatar comparison to Christian incarnation is not as clear as it might at first seem. There are clearly some important distinctions between the Hindu and Christian beliefs regarding incarnation.[3] First, Hindus claim many divine incarnations have appeared throughout history, while Christians believe Jesus is unique—the only begotten Son of God. The Christian Bible teaches that Jesus appeared “once to bear the sins of many” and “will appear a second time, not to deal with sin but to save those who are eagerly waiting for Him” (Heb. 9:28). So, second, we see that the purpose of avatars and the purpose of Christ are different. The avatars do not take away or bear sin. Third, in contrast to Hinduism, Christianity teaches that Jesus is Immanuel, God with us, and that He is still with us by the Holy Spirit. Lastly, the avatars in Hinduism appear for a time to balance out good and evil; in contrast, Jesus came and will come again to forever banish evil and sin.

So, Christianity’s belief in the incarnation of Jesus sets it apart from all other religions. The Creator became creation, the eternal entered time. As is sometimes said, there are many who would be god but only one God who would be man. Or, as Dietrich Bonhoeffer said, ”While we exert ourselves to grow beyond our humanity, to leave the human behind us, God becomes human.”[4]

4. Messiah Jesus

Muslims say they believe Jesus was the Messiah. In fact, the Quran explicitly refers to Jesus as the Messiah. One of the disagreements between Christians and Muslims, however, is what it means that Jesus was the Messiah. Muslims do not believe Jesus was God in flesh or that He was crucified.

It is true that the expectation presented in the Jewish Scriptures (Old Testament for Christians) for the Promised One seems almost impossibly diverse. How could any one person fulfill the many expectations? How could it make sense for the “Ancient of Days” (Dan. 7:9, 13, 22) to be a descendant of king David (2 Sam. 7:12-16; Is. 11:1; Jer. 23:5-6)?

The messianic expectations appeared to be nothing more than unrelated and random shards of glass. Yet, the New Testament authors, over and over, argue that Jesus is in fact the Promised One, the long-awaited Messiah, who fulfills the prophecies, patterns, pointers, and promises (2 Cor. 1:20). Jesus, who was from Nazareth (of all places) is believed to be the one who will crush the serpent of old and lead the way back into Eden, bless all the nations of the earth, and set up His righteous and eternal Kingdom. The New Testament helps us see that the Old Testament predictions work together to form an astounding, almost unbelievable, stained-glass picture of Jesus, the long-awaited, promised Messiah.

Regarding prophecy, there are several Old Testament passages we could consider. Here’s a sample:

- His appearance will be disfigured (see Isaiah 52:14 and Matthew 26:67).

- He will be despised and rejected (see Isaiah 53:3 and John 11:47-50).

- He will take sin upon Himself (see Isaiah 53:4-6, 8 and 1 Corinthians 15:3).

- He will be silent before oppressors (see Isaiah 53:7 and Matthew 14:60-61).

- He will be assigned a grave with the wicked and with the rich in His death (Isaiah 53:9 and Mark 15:27-28, 43-46).

- He will be a descendant of David (see 1 Chronicles 17:11-14 and Luke 3:23, 31).

- He will be born in Bethlehem (see Micah 5:2 and Matthew 2:1).

- He will be preceded by a messenger (see Isaiah 40:3-5 and Matthew 3:1-2).

- He will have a ministry of miracles (see Isaiah 35:5-6 and Matthew 9:35; 11:4-5).

- He will enter Jerusalem on a Donkey (see Zechariah 9:9 and Matthew 21:7-9).

- His hands and feet will be pierced (see Psalm 22:16 and Luke 23:33).

- He will be hated without reason (see Psalm 69:4 and John 15:25).

- His garments were divided, and lots were cast for them (see Psalm 22:18; John 19:23-24).

- His bones were not broken (see Psalm 34:20 and John 19: 33).

- His side was pierced (see Zechariah 12:10 and Jn. 19:34).

- He, the Mighty God, was born (see Isaiah 9:2-7 and Matthew 1:23).

Christianity is set apart from all other world religions because it says that Messiah Jesus, who is God incarnate, “died for our sins in accordance with the Scriptures” (1 Cor. 15:3).

5. The Resurrection

Christians believe that Messiah Jesus died as predicted, but that He didn’t stay dead; He rose, conquering sin and death. Christians believe that the resurrection of Jesus is the firstfruits of more to come. The resurrection of Jesus is like the down payment with a whole lot more to follow. He is the “test of concept” that proves that God will one day soon set the world aright.[5]

So, Christians believe time is going somewhere. The world itself groans to be fixed, and the Bible says that the resurrection of Jesus proves it will be fixed.

6. Historical Evidence

Christians do not base their beliefs on a dream wish. There are legitimate historical grounds for their beliefs. This sets Christianity apart from all other religions. Now, some other religions claim historical and archeological support, but the evidence for Christianity is much more convincing.

So, for instance, Douglas Groothuis has said, “The New Testament witness is far better established historically than the revisionism of the Quran.”[6] The New Testament documents are amazingly historically reliable. “Nearly 100 biblical figures, dozens of biblical cities, over 60 historical details in the Gospel of John, and 80 historical details in the book of Acts, among other things, have been confirmed as historical through archaeological and historical research.”[7]

Further, we can gather a substantial amount of information about Jesus through nonbiblical historical writers. From Pliny, Tacitus, Josephus, Lucian, Thallus, and Celsus, we see Jesus clearly existed and had a brother named James who was killed when Ananus was High Priest. Jesus was known to be some kind of wonderworker, wise man, and teacher. Yet, He was regarded by His followers to be divine. He was crucified under Pontius Pilate during the reign of Tiberius, and His crucifixion seems to have been accompanied by a very long darkness. Surprisingly, His crucifixion didn’t squelch the Christian movement.[8] Historical writings outside of the New Testament corroborate the accuracy of the New Testament.

The English philosopher Antony Flew, while not a believer in the resurrection of Jesus, said, “The evidence for the resurrection is better than for claimed miracles in any other religion. It’s outstandingly different in quality and quantity.”[9] Not only does the historical evidence point in the direction of Christianity, but the positive historical impact does too. We’ll look at that in “What sets Christianity apart” (part 3).”

Go to Part Two three here.

Notes

[1] E.g., Zeus, Poseidon, and Apollo.

[2] The New Testament repeatedly teaches that Jesus is God in flesh. Jesus and the New Testament writers over and overclaim Jesus’ divine nature. We see the creedal formula “Jesus is Lord” (1 Cor. 12:3; Phil. 2:11). “Lord” was used in the LXX to translate the divine name, so this designation very often equates Jesus with God. Jesus’ title is “Son of God” which implies He is of the same nature as God (Matt. 11:27; Mk. 12:6; 13:32; 14:61-62; Lk. 10:22; 22:70; Jn. 10:30; 14:9). Jesus is eternally preexistent (Jn. 1:1; Phil. 2:6; Heb. 13:8; Rev. 22:13). He has authority to forgives sins (Mk. 2:5-12; Lk. 24:45-47; Acts 10:43; 1 Jn. 1:5-9). He is even explicitly referred to as “God” (Matt. 1:21-23; Jn. 1:1-14; Titus 2:13; 1 Jn. 5:20; Rom. 9:5; 2 Pet. 1:1). And Jesus was condemned for who He claimed to be (Mk. 14:61-64; Jn. 8:58-59). Yet, the writers say it is right to worship Him (Matt. 2:11; 14:33; 28:9; Jn. 20:28; Heb. 1:5-9; Rev. 5). So, Jesus claimed to be the Lord and the New Testament confesses Him to be Lord. The Early Church taught that Jesus was God, too. Ignatius of Antioch (c. 50-117) said in his Letter to the Ephesians, “Our God, Jesus the Christ, was conceived by Mary according to God’s plan, both from the seed of David and of the Holy Spirit” (18.2 cf. 19.3; Letter to the Romans, 3.3; Letter to Polycarp, 3.2). Polycarp of Smyrna (c. 69-155) said, “The Son of God Jesus Christ, build you up in faith and truth…, and to us with you, and to all those under heaven who will yet believe in our Lord and God Jesus Christ and in his Father who raised him from the dead (Philippians 12.2). Justin Martyr (100-165) said, “Christ being Lord, and God the Son of God” (Dialogue with Trypho, 128), and he said that he would “prove that Christ is called both God and Lord of hosts” (Dialogue with Trypho, 36). We also have early archeological evidence from around 230AD. Ancient remains of an early church were discovered in the Megiddo prison in Israel. The church has ornate religious mosaics and an inscription that says, “God Jesus Christ” (Vassilios Tzaferis, “Inscribed ‘To God Jesus Christ,’” 38-49 in Biblical Archaeology Review March/April 2007 Vol 33 No 2).

[3] Kyle Brosseau, “How to Explain the Incarnation to Hindus.”

[4] Bonhoeffer, Ethics, 84 as quoted in Biblical Critical Theory 360.

[5] “The resurrection raises our consciousness to a new set of possibilities in this world and shows us that the way things are is not the way they will always be” (Christopher Watkin, Biblical Critical Theory, 442). “The resurrection is not a one-time happening but the beginning of a new and ongoing age.” (Ibid., 457).

[6] Douglas Groothuis, Christian Apologetics: A Comprehensive Case for Biblical Faith, 664.

[7] Holden and Geisler, The Popular Handbook of Archaeology and the Bible, 181.

[8] See Boyd and Eddy, Lord or Legend?, 135.

[9] See Groothuis, Christian Apologetics, 583.

* Photo by Willian Justen de Vasconcellos

What Is Success As A Church?

It can be easy to point out what is wrong in the church, but what are we even supposed to be aiming for? What does success look like? Church bloat is not the aim. Increasing the number of people who come to sit in a church building once a week is not the goal.

What is the Mission of the Church? by Kevin DeYoung and Greg Gilbert is a helpful book. They say, “The mission of the church—as seen in the Great Commissions, the early church in Acts, and the life of the apostle Paul—is to win people to Christ and build them up in Christ. Making disciples—that’s our task.”[1]

Success looks like more people loving Jesus and loving and living like Jesus. Success is making apprentices of Jesus who:

1. Go into the world with the good news of Jesus to make disciples.

How is this measured? Mature disciples will be regularly spending time with their neighbors, peers, and coworkers. Mature disciples don’t mainly spend their time in a church building, but being the church in the world. The goal is for Christians to obey the missional mandate. Faithful disciples don’t practice invitation; they practice evangelization.[2]

Instead of one person sharing the good news of Jesus from a stage once or twice a week, we’re working towards all people, all the time; everyone, everywhere. The goal of the church is to make disciples who, in turn, make disciples. Not fans. The goal is not getting more people into a building. The goal is sending more people out into the world.

2. Grow in maturity in word and deed.

How is this measured? Mature disciples will be regularly practicing the grace of the spiritual disciplines. It’s not just about sitting in a service but doing the things the Lord has called us to do. We can know a lot of things about Jesus and even say, “Jesus is Lord,” and yet contradict what we know and say by our lives.[3] If Jesus is Lord, we must listen and obey (Luke 6:46).

Maturity is not knowledge-based; it’s obedience-based. Knowing must lead to doing. Experientially loving God and tangibly loving our neighbors is vital. We don’t count consumers. We count disciples.

3. Give their time, talents, and treasure.

Mature disciples will regularly serve their local community and practice hospitality.[4] Notice, this is not church building centric. Mature disciples serve Christians and non-Christians (Gal. 6:10) where they work, live, and play.

Maturity is when you serve God in the way He has gifted and called you, not in the way that society expects you to. Taking ownership of your mission is a mark of maturity. The goal is not hoarders. The goal is giving away.

I believe we should encourage more service in the surrounding community and less in the church building. We should see that as more needed. May we be salt and light in our community and neighborhoods, and less about the industrial complex of the “church.” “Serving” does not equal serving in the church. I am sick of hearing pastors guilt people into serving in the church building. Pastors are sometimes guilty of telling people to essentially hide there light in a bushel. But, if you know the song, it says, “Hide it under a bushel? No!”

Serve and love the people where you are. We want people staying in their bowling league, with their coworkers, neighbors, and friends even if it means not going to the second Bible study or being on the tech team. We would much rather people practice hospitality than be on a hospitality team.

4. Gather together to encourage and be encouraged.

Mature disciples will be regularly gathering in community to practice the “one another passages.” Mature disciples—male and female, theologically trained or not—will be regularly using their spiritual gifts to build up the body of Christ.

Maturity is gathering and building up other believers and purposely scattering to bless the broken world that needs Jesus’ love. Maturity isn’t about attendance. It’s about intentionally spurring those in your life on towards love and good works (Heb. 10:24). The goal is incarnation, not isolation.[5]

Our Metrics Must Match Our Goals.

If the four practices above are our growth goals, there are various implications. We must create different structures to best reach those goals.

We all have things we value. If you walk into my house, you will see certain things that my family values. You will see that my wife and I value books. If you walk into my son’s room, you will see that he values Legos and books. We all have things where we live that show what we value.

What do we “see” at the gathering of the church? And what does what we see communicate about what we value? Do we value real, lived-out, day-in, day-out, discipleship? Or do we value budgets, buildings, branding, platforms, programming, and pizzazz?

I believe we are perfectly designed to obtain our current results. But, sadly, I don’t think the things we do result in disciples who make disciples. I don’t think our metrics do a good job of measuring discipleship, let alone the 2 Timothy 2:2 commission.[6]

What success looks like must change if we are to resemble our Savior. Our aim must shift if we want the church to reflect Jesus’ intent. Jesus’ clear emphasis was on making disciples who make disciples. “Jesus poured His life into a few disciples and taught them to make other disciples. Seventeen times we find Jesus with the masses, but forty-six times we see Him with His disciples.”[7]

The mission of the church is not to gather a crowd. The mission of the church is to make disciples who make disciples.

Notes

[1] Kevin DeYoung & Greg Gilbert, What is the Mission of the Church?, 63.

[2] Christians are called to share the good news of Jesus with people. The Bible never tells us to invite people to church (e.g., Matt. 5:16; 10:32-33; 28:18-20; Mark 8:38; 16:15; Romans 1:16; 10:14-17; 15:18; 1 Cor. 9:19-23; 1 Cor. 4:1-2; 10:33; 2 Cor. 5:20; 1 Peter 2:12).

[3] The Lord desires that Christians (who are followers of Christ, after all) be agents of peace (Matt. 5:9), partiers with the poor (Lk. 14:13-14) and helpers of the poor (Gal. 2:9-10), ministers of reconciliation (2 Cor. 5:18-19), protectors of orphans and widows (Is. 1:17; James 1:27), fighters of injustice (Is. 58:6), and people of mercy (Matt. 5:7).

[4] Hospitality is important because it’s been a Christian value throughout Christian history, and it’s a strategic way to be the church on mission. This value is demonstrated by regularly sharing meals with others (including those who are different and needy), intentionality in connecting with our neighbors, and prayerful pursuit of loving friendships where God has planted us.

[5] I believe a few pivots are needed. Here are a few examples: The criteria of faithfulness and maturity should not be going to a building on Sunday and sitting in a hour/hour-and-a-half service. And for the “super Christian” serving the church by watching the kids, being a greeter, or giving some money to the church. Instead, being the salt and light church of God on Monday and throughout the week is the criteria. No bifurcation in life. We are the church. We don’t go to church. Church is not on Sundays.

[6] 2 Tim. 2:2 says, “And the things you have heard me say in the presence of many witnesses entrust to reliable people who will also be qualified to teach others.”

[7] Dann Spader, Four Chair Discipling, 36. “These few disciples, within two years after the Spirit was poured out at Pentecost, went out and “filled Jerusalem” with Jesus’ teaching (Acts 5:28). Within four and a half years they had planted multiplying churches and equipped multiplying disciples (Acts 9:31). Within eighteen years it was said of them that they “turned the world upside down” (Acts 17;6 ESV). And in twenty-eight years it was said that the gospel is bearing fruit and growing throughout the whole world” (Col. 1:6). For four years Jesus lived out the values He championed in His Everyday Commission. He made disciples who could make disciples!” (Dann Spader, Four Chair Discipling, 36). Also, “Jesus gives more than 400 commands in the Gospels and more than half of them are disciple-making commands.” (Ibid., 37).

*Photo by Helena Lopes

What sets Christianity apart? (part 1)

It makes sense to consider religious claims. “Even if religion makes no sense to you, you need to make sense of religion to make sense of the world”[1] because the world is religious. It always has been. One author says, “Evidence is abundant that human beings are incurably religious.”[2]

It especially makes sense to consider the claims of Christianity. Douglas Groothuis makes a good argument for the stakes being higher for Islam and Christianity.[3] This is because some of the other religions offer types of do-overs through reincarnation. If you didn’t get it right the first time, you can try again in your next life. Christianity and Islam believe it is one and done. So, it makes sense to investigate the religions that offer no redos first.

That being said, there are many world religions. There are also many irreligious people.[4] And both religious and irreligious people can be very kind and good. So, what sets Christianity apart?

What World Religions Have in Common

World religions and even atheism are asking similar questions; they are just giving different answers. Each religion articulates:

- a problem

- a solution

- a technique for moving from the problem to the solution

- an exemplar who charts the path from problem to solution[5]

There are 9 things that most major world religions have in common. Most religions have some type of…

- Higher Power

- Life After Death

- Prayer or Meditation

- Transcendence

- Community

- Moral Guidance

- Service to the poor

- Purpose

- Founder/Central Figure

Are All Religions Basically the Same?

Are all religions basically the same? In short, no. All religions are not basically the same. Even if they do have similarities in places.

As Stephen Prothero, who is not a Christian, has demonstrated, each religion “offers its own diagnosis of the human problem and its own prescription for a cure. Each offers its own techniques for reaching its religious goal, and its own exemplars for emulation.”[6] We should not lump all religions together in one trash can or treasure chest. Instead, we should start with a clear-eyed understanding of the fundamental differences in both belief and practice of those religions.[7]

Christians, however, believe in something referred to as “common grace.” That is, God gives certain gifts to all humans (Matt. 5:45) and all humans are made in God’s image. Humans can arrive at certain correct conclusions apart from God’s divine revelation. So, while all religions are not all basically the same and not all correct, they can have more or less correct insights into various subjects.

So, Douglas Groothuis has said, “Although Christianity cannot be reduced to a common core that it shares with other religions, it can still find some common ground with respect to the individual beliefs held by other religions. Other religions are not completely false, even though their teachings cannot offer salvation and even though they must be rejected as inadequate religious systems or worldviews.”[8]

What Sets Christianity Apart?

We will look at ten significant aspects of Christianity that set it apart from all other religions.

1) Trinitarian Monotheism

“Trinitarian Monotheism”‽ What does that mean? Christians believe there is only one God and that this one God exists as three persons. God is triune (thee [tri] and one [une]). So, trinitarian refers to God’s three-in-one nature. Monotheism refers to there being one God. Mono comes from the Greek meaning “alone.” Theism refers to belief in god or gods (Theomeans “God” in Greek). So, monotheism refers to the belief in one God.

The Christian teaching on the three-in-one nature of God sets Christianity apart from all other religions. Islam, in contrast, teaches that God is a relational singularity. “Allah is distant; God is Immanuel. The differences between Allah and the God of Christianity are vast because the nature of Allah as one cannot compare with the richness of the loving Trinity.”[9] Allah is incapable of possessing a love like the love that Yahweh has within Himself as Trinity. “Allah is complete oneness, love cannot be a part of his essence and therefore, no matter how loving he chooses to be, his nature is not founded on this love, and thus it cannot compare to the love of Yahweh, the God who is love.”[10] God, being love and Himself teaching us to love, is unprecedented.

The triune nature of God shows that He is relational, loving, self-giving, and personal. God is not just some distant, cosmic force. He has personhood. He has existed in all eternity past in a loving relationship, strange to say, with Himself. God amazingly calls us to join in that relationship with Him (Jn. 17:20ff). He recreates us in His image and welcomes us as His sons and daughters. God welcomes us to have communion with Himself.

If the Trinity is true as the Bible articulates, then God is relational, relational to the core. If God is triune, then Jesus is God. That means that God walked among us as a human. That means God can relate to what we face (Heb. 4:15). He is not a distant deity. If God is a Trinity, then that means that in Jesus, the divine experienced death. If God is a Trinity, and Jesus shows us what God is like in full living color, then we can see God is good even if we can’t always understand His ways.

Christianity is set apart from all other religions by its understanding of the Trinity. But Christians believe the Trinity is actually articulated in the Jewish Scriptures.[11] Jesus, Christians believe, is like a light that brings visibility to what was already there.

2) Eternal Love

The Bible doesn’t just say that God is loving, though it does say that. The Bible says much more. It says, “God is love” (1 Jn. 4:8, 16). Love is deeply connected to God’s very being. This sets the Christian God apart from all other views of God. For love to truly exist, there must be relationship. The Bible, as we have seen, teaches that God is triune. Although we cannot fully grasp what that means, we do know it means God has for all eternity been in loving relationship. Because God is love, He cares about love and teaches us to love (1 Jn. 4:7).

The Apostle Paul says the Thessalonians have been “taught by God to love one another” (1 Thess. 4:9). “Taught by God” is one word in the Greek in which Paul wrote. There are no known occurrences of it anywhere in Greek literature.[12] Paul likely coined the term himself. God is love, and He teaches us how to love. Think of that phrase in the context of history. Think about what we learn about love from Greek mythology. Not a lot. Instead, we see gods at war and spreading chaos.

In reality, God is the only one fully qualified to teach on the subject of love, because love would not exist without Him. He is its author. He is its commentator, because you would not know how to love without His instruction. So then, God not only teaches you about love, but He also teaches you how to love. Therefore, to begin any discussion on the subject of love, the logical starting point must be with God Himself.[13]

Christianity is set apart from all other religions because Christians believe God is a God of love, eternal love.

Notes

[1] Stephen Prothero, God Is Not One: The Eight Rival Religions that Run the World—and Why their Differences Matter, 8. “Religion is not merely a private affair. It matters socially, economically, politically, and militarily” (Ibid., 7).

[2] Michael Peterson, William Hasker, Bruce Reichenbach, and David Basinger, Reason & Religous Belief: An Introduction to the Philosophy of Religion, 3.