The War of Art

I appreciate this from Steven Pressfield in The War of Art:

“The following is a list, in no particular order, of those activities that most commonly elicit Resistance:

1) The pursuit of any calling in writing, painting, music, film, dance, or any creative art, however marginal or unconventional.

2) The launching of any entrepreneurial venture or enterprise, for profit or otherwise.

3) Any diet or health regimen.

4) Any program of spiritual advancement.

5) Any activity who aim is tighter abdominals.

6) Any course or program designed to overcome an unwholesome habit or addiction.

7) Education of every kind.

8) Any act of political, moral, or ethical courage, including the decision to change for the better some unworthy pattern of thought or conduct in ourselves.

9) The Undertaking of any enterprise or endeavor whose aim is to help others.

10) Any act that entails commitment of the heart. The decision to get married, to have a child, to weather a rocky patch in a relationship.

11) The taking of any principled stand in the face of adversity.

In other words, any act that rejects immediate gratification in favor of long-term growth, health, or integrity. Or, expressed another way, any act that derives from our higher nature instead of our lower. Any of these will elicit Resistance.”

The Crash of the American Church?

Research shows that the “evangelical church” lost around 10 percent of her people in the last decade. There are many factors that are involved that have resulted in this decline. Further, most churches that are growing are just taking people from other churches, not converting people. The Great Evangelical Recession explores the factors involved in the decline of the church and offers suggestions for the future. I found the book helpful and thought-provoking.

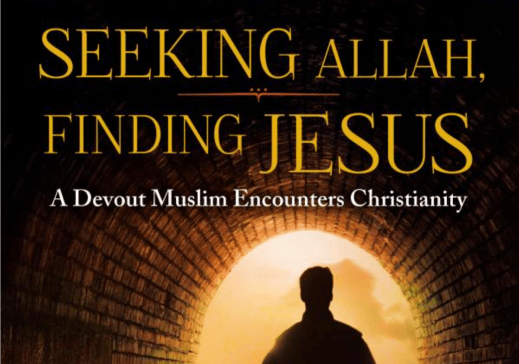

Nabeel Qureshi, Seeking Allah, Finding Jesus (a book review)

Hearing about Qureshi’ struggle as he thought about what it would mean to convert to Christianity was helpful. It will help me to be appropriately empathetic will discussing Christianity with Muslims. It is helpful to realize that “Muslims often risk everything to embrace the cross” (p. 253). I appreciated hearing his prayer: “O God! Give me time to mourn. More time to mourn the upcoming loss of my family, more time to mourn the life I’ve always lived” (p. 275). I also appreciated what he said about the cost of discipleship: “I had to give my life in order to receive His life. This was not some cliché. The gospel was calling me to die” (p. 278). Read More…

The Importance of Correct Hermeneutics

If we don’t understand things in their proper context there will be grave results. Let’s look at a few verses as an example and apply a skewed hermeneutical approach and see what the result is.

John 3:16 says, “God sent His Son” and we see that Jesus as God’s son is confirmed in other Scriptures. Take for example Romans 8:32. Or Hebrews 5:8 tells us that although Jesus “was a son, He learned obedience.” Luke 2:42 says that “Jesus increased in wisdom and in stature and in favor with God and man.”

So, it could be argued that Jesus, as God’s Son, was created and had to learn. After all, doesn’t “son” mean “son”?! Isn’t that the clear reading of the text? If the Bible says that Jesus is a “son” and “the firstborn of all creation” does that mean that Jesus is not eternal? Does it mean that He is a created being?

If we just look at the word “son” and extrapolate its meaning without understanding the context and the sense in which the author is using the word we can make very dangerous and false conclusions. Is Jesus a son in the sense of being a created being? No! That is the Arian heresy. We must understand what the author meant and we must use clear texts to help us interpret the less clear. A bad hermeneutical approach will lead to all sorts of false and destructive doctrines.

When looking at any doctrine it is important to understand a number of things. When looking at the sonship of Jesus for example, it is important to know the Old Testament and cultural importance of sonship. It is also important that other Scriptures are factored in. For example, John 1:1-14 and Colossians 1:15-17 show us that Jesus is not created but instead Creator.

So, “the obscure passage must yield to the clear passage. That is, on a given doctrine we should take our primary guidance from those passages which are clear rather from those which are obscure.”[1] Charles Hodge said in his Systematic Theology that

“If the Scriptures be what they claim to be, the word of God, they are the work of one mind, and that mind divine. From this it follows that Scripture cannot contradict Scripture. God cannot teach in one place anything which is inconsistent with what He teaches in another. Hence Scripture must explain Scripture. If a passage admits of different interpretations, that only can be the true one which agrees with what the Bible teaches elsewhere on the same subject.”[2]

Here are some important affirmations for biblical hermeneutics:

- We should affirm the unity, harmony, and consistency of Scripture and declare that it is its own best interpreter.[3]

- We should affirm that any preunderstandings which the interpreter brings to Scripture should be in harmony with scriptural teaching and subject to correction by it.[4]

- We should affirm that our personal zeal and experiences should never be elevated above Scripture (see Rom. 10:2-3).

- We should affirm that texts of Scripture must be interpreted in context (both the immediate and broad context).

- We should affirm that we must only base normative theological doctrine on clear didactic passages that deal with a particular doctrine explicitly. So, we should affirm that we must never use implicit teaching to contradict explicit teaching.

______________________

[1] Bernard Ramm, Protestant Biblical Interpretation: A Textbook of Hermeneutics, 37.

[2] Charles Hodge, Systematic Theology, Vol. 1, Introduction, Chapter VI, The Protestant Rule of Faith.

[3] See “The Chicago Statement on Biblical Hermeneutics,” Article XVII.

[4] See Ibid., Article XIX.

Mike Kuhn, Fresh Vision for the Muslim World (a book review)

[Kuhn, Mike. Fresh Vision for the Muslim World. Downers Grove, IL: Intervarsity Press, 2009.]

Kuhn proceeds then to talk about the theological differences between Christianity and Islam. For instance, “the essence of the Christian faith—God became human being in Christ—is diametrically opposed to Islamic faith” (69). There is also a vast difference in the view of what constitutes humanities problem and thus our view of salvation is different. Islam teaches that “individuals are neither dead in sin nor in need of redemption; rather, they are weak, forgetful, and in need of guidance” (78). The heart of the difference between Islam and Christianity is how man is put right with their Creator (81).

In chapters seven through nine, Kuhn reminds us that Jesus’ concern was not with “the geopolitical state of Israel during his earthly ministry. His concern is with his kingdom—the kingdom of heaven” (120). The place of the state of Israel is a subject filled with tension for many Muslims and Christians alike but it is also a very important and practical subject. So, we must seek God and His Scripture for wisdom, we must understand Jesus’ words (130, 171). Kuhn points out that the need of the entire world is to see “the manifestation of the kingdom of Jesus in his people” (158, italics mine), not in an earthly nation. As we have seen, we are to love our neighbors and part of loving someone is understanding them, their history, their perspective, their past hurts.

Chapter ten talks about jihad and explains that not all Muslims understand jihad in the same way, some have a spiritualized understanding of jihad (e.g. 199). So, it is important to understand that Muslims, like Christians, are not all the same. In fact, “the primary concerns of most Muslims are similar to ours—raising their children, providing for their children’s education, saving for that new car or outfit… We must exercise care not to be monofocal in our understanding of Islam” (187). Chapter eleven challenges us to faithfully speak for Jesus and live for His Kingdom and not our own. In part 5, chapters twelve through thirteen, we see steps to incarnation and what it means to live missionally (see esp. 225).

I believe Kuhn could have had more Scriptural argumentation at places but I realize his book was not meant to be exhaustive. However, I agree with most of what he wrote and believe it is truthful. That is, I believe Kuhn made a cogent case in what he said. I also appreciate that he gave a recap of each chapter, it helped give the book clarity.

Stylistically, I appreciate that Kuhn covered many different topics yet did not lose the focus of the book. For example, he introduced incarnation at the beginning (8) and then weaved it through the rest of the book (see e.g. 13, 16, 75, 85. 242). What is needed Kuhn pointed out, though sadly rare, “is an extended hand, a caring smile, someone who is willing to go the extra mile to help someone in need” (259) (cf. Matt. 5:13-16; Jn. 13:35; 1 Cor. 10:33).

I appreciate Kuhn’s reminder that “The kingdom of Jesus as opposed to empire is not concerned in the least about the political boundaries of a country. It is a reality that overlays the political boundaries” (256). We must remember that the Roman Empire came and went, but Jesus’ Kingdom is eternal (254) (cf. Jn. 18:36). Kuhn’s challenge is timely, he says, “if Western Christians are able to bid farewell to our fortress mentality, we will find that our countries have already become exceedingly accessible and potentially fruitful mission fields” (244). Kuhn further points out that if American Christians are overly aligned with their governments’ policies then their missional impact will likely be impacted (241). Instead, as Christians, Jesus should be our King and His policies should hold ultimate sway. The real hope of the Muslim world, and the Western world for that matter, is not democracy, it the diffusion of the good news of Jesus the Christ and the establishment of His reign (218).

As Muslims grow increasingly suspicious and fed up with the violent response of Islamists, they are beginning to look for alternatives. Some are finding their alternative in secularism. Others are turning to materialistic pleasure. Will we as Christ-followers have anything to offer them? (214-15)