Back to Virtue by Peter Kreeft

I recently read Peter Kreeft’s book Back to Virtue. Kreeft is a Roman Catholic philosopher, theologian, apologist, and a prolific author. He is a professor of philosophy at Boston College and The King’s College.

Here are some quotes from Back to Virtue that stuck out to me:

“We control nature, but we cannot or will not control ourselves. Self-control is ‘out’ exactly when nature control is ‘in’, that is, exactly when self-control is most needed” (Peter Kreeft, Back to Virtue, 23).

“Nothing is so surely and quickly dated as the up-to-date” (Peter Kreeft, Back to Virtue, 63).

“It is hard to be totally courageous without hope in Heaven. Why risk your life if there is no hope in Heaven. Why risk your life if there is no hope that your story ends in anything other than worms and decay” (Kreeft, Back to Virtue, 72).

“The only way to ‘the imitation of Christ’ is the incorporation into Christ” (Ibid., 84).

“There are only two kinds of people: fools, who think they are wise, and the wise, who know they are fools” (Ibid., 99).

“Humility is thinking less about yourself, not thinking less of yourself” (Ibid., 100).

“God has more power in one breath of his spirit than all the winds of war, all the nuclear bombs, all the energy of all the suns in all the galaxies, all the fury of Hell itself” (Ibid., 105).

“We can possess only what is less than ourselves, things, objects… We are possessed by what is greater than ourselves—God and his attributes, Truth, Goodness, Beauty. This alone can make us happy, can satisfy the restless heart, can fill the infinite, God-shaped hole at the center of our being” (Ibid., 112).

“The beatitude does not say merely: ‘Blessed are the peace-lovers,’ but something rarer: ‘Blessed are the peacemakers’” (Ibid., 146).

“There is only one thing that never gets boring: God… Modern man has… sorrow about God, because God is dead to him. He is the cosmic orphan. Nothing can take the place of his dead Father; all idols fail, and bore” (Ibid., 157).

“God’s single solution to all our problems is Jesus Christ” (Ibid., 172).

“An absolute being, an absolute motive, and an absolute hope can alone generate an absolute passion. God, love and Heaven are the three greatest sources of passion possible” (Ibid., 192).

Encouragement in Exile (A Sermon)

Intro

I want to say at the start that I understand it can be hard to sit there and be engaged. I’ve been there. I want to challenge you, however, to lean in and listen. The events we’re talking about here may be some 2500 years in the past but they have amazing significance today.

Plus, the book of Esther is an amazing book. It is a true work of literature. There is a heroine, suspense, irony, reversal, and surprising coincidences. Basically everything you’d want in a story.

Setting: Exile

The book of Esther tells “the story of events surrounding the rescue of the nation of Israel from the threat of extinction while it was in exile in Persia… The more profound and universal purpose of the story is to explain how God’s providence can protect his people.”[1]

Whoever you are, wherever you come from, and no matter where you are spiritually, this year has likely brought many challenges to you. I believe the book of Esther offers some much-needed perspective on things.

Chapters 1-2

As we saw the last two weeks, God’s people are in exile, under the reign of king Ahasuerus. Ahasuerus, as the King of Persia, has a ton of wealth. So he shows his wealth by having a party for 180 days (1:4).[2] With that much partying it is no wonder that he seems to be somewhat of a drunk and pushover. However, it appears that he’s trying to combat his pushover persona (but not his potential alcoholism!) with the help of his friends and so he makes an example of his wife Vashti who did not obey his every whim.

In Herodotus’ Histories, it says that that the “king of Persia could do anything he wished.”[3] And so, that’s what he did. He gets rid of his old wife and throws a lavish beauty pageant to find the most beautiful and pleasing bride in the kingdom (2:2-4). In somewhat of a Cinderella story, the king “fell in love” with Esther or at least more than all the other women and so he put the royal crown on her head and made her queen (v. 17).

Esther’s Exile

Israel is in Exile. God’s people are not in the Promised Land. They have a foreign ruler. And can you imagine, that ruler was allowed to do “anything he wished.”

Our Exile

We too are in exile, we too are not home. It may be different than Esther’s exile but we are in exile too. We see this truth in Scripture in various places. For instance, 1 Peter 1:1 talks about us being “elect exiles” and verse 17 tells us how we are to conduct ourselves throughout the time of our exile. First Peter 2:11 says, “Beloved, I urge you as sojourners and exiles to abstain from the passions of the flesh, which wage war against your soul.” Philippians 3:20 reminds us “our citizenship is in heaven, and from it we await a Savior, the Lord Jesus Christ.” Hebrews 13:14 says that “here we have no lasting city, but we seek the city that is to come.”

So, just as Esther was in exile, we as Christians are in exile too. This book is relevant and has a lot to encourage us in the midst of the challenges of exile.

More and more our exile is a very visible reality. The Public Religion Research Institute did a study on religious affiliation in America. Here are their findings:

“The American religious landscape has undergone substantial changes in recent years… One of the most consequential shifts in American religion has been the rise of religiously unaffiliated Americans… In 1991, only six percent of Americans identified their religious affiliation as ‘none,’ and that number had not moved much since the early 1970s. By the end of the 1990s, 14% of the public claimed no religious affiliation. The rate of religious change accelerated further during the late 2000s and early 2010s, reaching 20% by 2012. Today, one-quarter (25%) of Americans claim no formal religious identity, making this group the single largest ‘religious group’ in the U.S.”[4]

The study also found “about two-thirds (66%) of unaffiliated Americans agree ‘religion causes more problems in society than it solves.” They also “reject the notion that religion plays a crucial role in providing a moral foundation for children.”[5]

It is not just America, however, that is becoming increasingly less affiliated. The Church in America also has less and less commitment.

One recent study conducted by Barna Group for the book Faith for Exiles found that out of the around 1,500 people between the ages of eighteen and twenty-nine that grew up in the church (as Christians) the majority no longer go to church. 22% are now considered “ex-Christians.” 30% may identify themselves as Christians but they no longer go to church. 38% describe themselves as Christians and have attended church at least once in the last month but do not have the core beliefs or behaviors associated with being a disciple of Jesus. Only 10% were found to be regularly involved in the life of the church, trust in the authority of Scripture, affirm the death and resurrection of Jesus, and express a desire for their faith to impact their world.

Dedicated Christians are more in more considered odd. Christians are more and more on the fringes of society. If things don’t change, these trends will just continue in the future. The reality of our exile status will be felt more and more.

So, friends, Esther has a lot to teach us about our exile. Let’s go to the first scene…

1. Haman’s Plot (Ch. 3)

Scene 1 starts with Haman, the antagonist or bad guy of the story,[6] being promoted (3:1). It seems like he’s promoted because the beauty pageant was his idea.

Haman soon became furious at a Jewish man named Mordecai because he would not bow down to him. But instead of just taking it out on him, Haman wanted to destroy all the Jews throughout the whole kingdom (3:5-6). So, we see a big problem introduced in the plot.

Haman decided which day the Jews should be destroyed on by casting a lot. Lot is the word “pur,” so that’s where the name Purim, the Jewish holiday, comes from. Because Haman cast lots to decide what day the Jews would be destroyed on. However, as Proverbs 16:33 reminds us the lot (pur) is cast into the lap, but its every decision is from the Lord. And so we see, even when the name of the LORD is not mentioned we see God is sovereign over human affairs and He will keep His promises to protect and bless His people. He will not let His people be wiped out.

Haman was so eager to destroy the Jews that he offered to pay the king ten thousand silver talents, the

equivalent of eighteen million dollars today,[7] of his own money if the king would allow him to destroy the Jews. The king agreed and a decree was sent and Haman and the king sat down to drink (again).

Then in Esther 3:13-15 it says, “Letters were sent by couriers to all the king’s provinces with instruction to destroy, to kill, and to annihilate all Jews, young and old, women and children, in one day, the thirteenth day of the twelfth month, which is the month of Adar, and to plunder their goods. A copy of the document was to be issued as a decree in every province by proclamation to all the peoples to be ready for that day. The couriers went out hurriedly by order of the king, and the decree was issued in Susa the citadel.”

Things clearly are not looking good. What can possibly be done? Let’s look next at…

2. Esther’s Plan (Ch. 4-5)

In scene 2 we see Mordecai appeal to Esther (Ch. 4). Mordecai hears about Haman’s plot to kill the Jews and so he talks to Esther about it. Mordecai says, in Esther 4:12-14, “Do not think that in the king’s palace you will escape any more than all the other Jews. If you keep silent at this time, relief and deliverance will come for the Jews from another place, but you and your father’s house will perish. And who knows whether you have not come to the kingdom for such a time as this?” (4:12-14)

Imagine how scary that must have been for Esther. She could be totally rejected, she could be killed. Yet she moved forward. She just had one thing to say to Mordecai. She said: “Hold a fast on my behalf, and do not eat or drink for three days, night or day. I will also fast. Then I will go to the king, though it is against the law, and if I perish, I perish” (4:15-16).

In the next scene, scene 3, we see Esther before the king (Ch. 5:1-8). Esther has her first banquet with the King. Esther goes to the king and says, “Please join me for a feast that I prepared and invite your friend Haman too” (5:4). Then, at the feast, Esther says let’s feast again tomorrow and we’ll talk more then (5:8).

(It’s funny, is Esther delaying? Is she nervous? Is she buttering him up? We don’t know…)

In scene 4 we see Haman’s exaltation and anger (Ch. 5:9-14). After the feast, Haman leaves and he is joyful and glad. But then he sees Mordecai on the way home and he doesn’t rise in respect before him or tremble before him. And so Haman is ticked off and his wrath is renewed (5:9).

Haman was able to contain himself, however, and made it home. When Haman was home he had his friends over and was talking with them and his wife. He was recounting how good everything was going and he told them that he even got to hangout with the king and his new bride (5:12). “However,” he said, “It’s all pointless to me, so long as I see Mordecai still alive” (cf. 5:13).

So, his wife and friends said, “Build a frame six-stories high and have Mordecai executed on it.” When Haman heard that idea, he said, “That’s it!” And with great excitement he had the structure built so that the entire city could see Mordecai his enemy impaled.

Haman was haughty. He thought he could have Mordicai and all the Jews murdered and get away with it. But, next we see…

3. Haman’s Downfall (Ch. 6-7)

In scene 5 we see Mordecai’s triumph and Haman’s fall (Ch. 6-7). As we flash to scene 5, we see Esther getting herself together and preparing for her talk with the king.

But, the king couldn’t sleep. So, he did what any self-respecting king would do, he asked for a bedtime story.

The king gave orders for the book of memorable deeds to be brought and read to him (6:1).[8] And before the

king got bored and fell asleep the story was recounted how Mordecai protected the king from an assassination attempt (6:1-2).

And the king said, “What honor or distinction has been given to Mordecai for what he did?” The king was told that “Nothing had been done” (v. 3).

That’s when, guess who walked in?…

Haman walks into the king’s palace to speak to the king about having Mordecai impaled.

However, before Haman could ask his question, the king asked him a question. The king said to Haman: “What should be done to the man whom the king wants to honor?” (v. 6)

And Haman thought to himself, “Who would the king want to honor more than me?!” (v. 6).

So Haman said to the king, in 6:6-9, “For the man whom the king wants to honor, I would get the royal robes out, and the best horse that the king has, and your favorite royal crown. And I would give it to him. And I would have a parade for him and lead him through the street and say: ‘This is what happens to the person that the king wants to honor!’”

Then the king said to Haman, “Great! Good ideas! Now hurry; and go do all that you just said for Mordecai the Jew! Do everything that you just said! (v. 10)

Wow.

Haman clearly is not doing very well.

Haman eventually goes home (“rough day at the office”). And his wife and friends concur that this is not a good situation… Obviously.

Haman can’t hide in shame. He has a feast to attend, Esther’s special feast to which he is a very special guest.

At the feast, Esther makes a request of the king. She says, in chapter 7 verse 4, “Please let me keep my life and the life of my people.” “For we have been sold, I and my people, to be destroyed, to be killed, and to be annihilated” (7:4).

Then king Ahasuerus said to queen Esther, “Who is he, and where is he, who has dared to do this?!” And Esther said, “A foe and enemy! [Pause for effect…] This wicked Haman!” (7:6)

Then Haman was terrified before the king and the queen.

The king stood up in his anger from his wine-drinking and went into the palace garden, but Haman stayed to beg for his life from queen Esther. But, the king returned from the garden just as Haman was falling on

the couch where Esther was. And the king said, “Will he even assault the queen in my presence?!” (7:8)

At this point, Haman had no hope.

One of the servants said, “The six-story structure that Haman prepared for Mordecai is standing at Haman’s house ready to go.” (7:9)

And so, Haman was executed on the stand that he had prepared for Mordecai (7:10).[9]

Wow. What a reversal. What unexpected deliverance. Of course, the stories not quite through but that’s all we’re covering until next week. So, let’s look at the…

Closing Scene (Takeaways Until Next Time)

There is so much to be gleaned. There are four takeaways I want to spend the remainder of time looking at.

1. God uses People

Esther is the unexpected star of the story. Ironically, Esther means, “star” and she was the star. There are 37 references to Esther by name. “Esther is an orphaned, exiled female. She is a most unlikely leader. Her only qualification is that she has won a beauty contest. Yet she joins a long line of unlikely heroes in the history of Israel.”[10]

God uses unlikely people and deliverers in unexpected ways. It’s actually kind of His standard operating procedure. God used Moses, a man with a stammering tongue. God anointed David to be king, the youngest and most unexpected of his brothers. God uses small armies to bring deliverance. God puts His treasure in jars of clay so that it will be clear that the power and glory belong to Him (see e.g. 2 Cor. 4:7). And God uses the foolishness of the cross to bring salvation and shame the “wise” (see 1 Cor. 1:18-31).

Where did the rescue come from? Esther? Mordecai? Xerxes? God? God uses means to accomplish His ends!

What we do matters. Our lives and our decision matter eternally. They ripple through the corridors of time. There was and never will be a meaningless moment. John S. Dickerson in his book,The Great Evangelical Recession, has said:

“The stakes are eternal. The victims or victors are not organizations or churches, but souls that will live forever… We can feel a bit like Frodo, the hobbit, in The Lord of the Rings. We are tiny creatures entrusted with an impossible task—to rescue humanity from unthinkable evil… All we have to decide is what to do with the time that is given to us.”[11]

My family used to live in the D.C. area. We saw where the plane hit the Pentagon on September 11th. Leah and I have been to New York city and have seen where the Twin Towers used to be. We have been by the monument in Pennsylvania that commemorates the passengers in the plane that went down in on September the 11th instead of careening into the White House.

Think about the decisions that were made in that plane on that fateful day. Think about the weightiness of those decisions. Think about the effect of those decisions upon themselves and upon all of America.

We don’t often see the impact of our decisions that starkly but what we do or don’t do matters. It matters for us. It matters for others.

What we do matters. It matters eternally. God uses mere humans as His mouthpiece. God uses humans to do His will.

Friends, our lives matter, our actions matter, our voices matter.

If we knew a millionth of the magnitude of our lives we’d be moved to wonder. Our lives and our every action have significance because this world and this life is not all there is.

And for Christians, this is multiplied ten-fold. We are mouthpieces, ambassadors, commissioned by the one true God.

God gives us wit, wisdom, and human will. Will we use what God has given us? Will we rise to the occasion and work to reach this lost world with the good news of Jesus? Or, will we just sit back? As we’ve seen with Esther, it won’t be easy and it will be scary but who knows whether you have not come to this place in your life and this place in history for such a time as this (cf. 4:14)?!

Friends, let’s live fierce purposeful lives because we have purpose. Our lives matter more than we can know.

That, too me, is very challenging and very encouraging. The other side of the coin, however, is very comforting and encouraging too. Let’s look at that now…

2. God is Sovereign

Haman has such hatred of the Jews he contrives of a pogrom and even bribes the king the modern equivalent of somewhere around $18,000,000 so that he can exterminate them. It does not look like rescue is going to come. How could it when the wicked one in power is willing to go to such lengths to destroy?! What hope was there really?…

Friends, if God’s not sovereign and He doesn’t save then that leaves it to you to save and be sovereign. If God is not Lord, then you have to be lord. It falls to you. Everything falls to you. You then have to govern the universe, at least your universe. You then have to rescue yourself or there will be no rescue…

In Esther there are 250 appearances of the Hebrew word for “king” or “to rule” and zero explicit references to God. The only other book that doesn’t explicitly mention God is the Song of Songs. In Esther it looks like Satan, “the ruler of this world” (Jn. 12:31 cf. Eph. 2:2), is in charge. But, he’s not. There’s someone unseen and unmentioned who really rules. And it’s Yahweh, the Creator and all-powerful One. He is God. He is in charge. We may not see Him. But we know Him. And we know He’s the boss.

The truth is though, from our perspective God is often not in view. We don’t see Him. And it looks like there is no hope. No rescue. We only see ourselves and earthly rulers. We either tremble in fear or we place our hope in them or we do both. We often think about earth and those who seemingly rule on earth. But the reality is, as Esther shows us, that there is someone orchestrating everything behind the veil…

In the book of Esther we see that God is present even when it seems like He’s not. “The book of Esther asks us to trust in God’s providence even when we can’t see it working. That requires a posture of hope, to believe that, no matter how horrible things get, God is committed to redeeming his good world and overcoming evil.”[12]

And so, we need to trust like Mordecai. We must not bow down to any earthly powers. And we need to fast and pray and ask others to fast and pray in times of need. We need to rely on God even when He seems absent. We need to lay our lives down in service to God with a heart that says, “If I perish, I perish” (Esther 4:16). Especially as we consider that Jesus did perish to purchase our salvation.

As Mark Dever has said, “How could little orphan Esther end up as queen, Mordecai as prime minister, and the exiled Jewish people in prosperity, popularity, and safety!”[13] Only because God is the one truly on the throne of the universe. How could salvation come through the death of Messiah Jesus, because Jesus is Lord and the Son of God.

Our hope is in a Ruler, in a King. But, He is no earthly ruler. He is the King of kings, and Lord of lords. He is the one and only Sovereign. As David Platt has said, “This world is not a democracy. This world is a monarchy, and God is the King.”

Sometimes when things look the worst, is when God shows His power the most. Actually, at the end of all things, when Jesus comes back, things are going to look very bad and be very bad. But then Jesus is going to show up on the scene. And He’s going to vanquish His foes. He will arrive not on a lowly donkey but on a white horse of war. He will destroy His enemies with the sword of His mouth (Rev. 1:16; 19:15, 21). There will be no Haman, no human, and no supernatural force to stand in His way.

Elliot Clark said this in his helpful book, Evangelism as Exiles:

“Hope for the Christian isn’t just confidence in a certain, glorious future. It’s hope in a present providence. It’s hope that God’s plans can’t be thwarted by local authorities or irate mobs, by unfriendly bosses or unbelieving husbands, by Supreme Court rulings or the next election. The Christian hope is that God’s purposes are so unassailable that a great thunderstorm of events can’t drive them off course. Even when we’re wave-tossed and lost at sea, Jesus remains the captain of the ship and the commander of the storm.”[14]

That leads us to our next consideration…

3. God Punishes His Enemies

Another important thing Esther teaches us is that God always punishes His enemies. We also see that God will certainly deliver His people.[15] Therefore, we can be comforted in our struggles, courageous in our obedience, and confident and joyful in our waiting.[16]

It must be said, however, that if you are an enemy of God, that is bad news. The worst news.

But we can have hope. Even though we’re all naturally enemies of God because of our wrongdoing. We can have hope because…

4. God Saves in Unexpected Ways

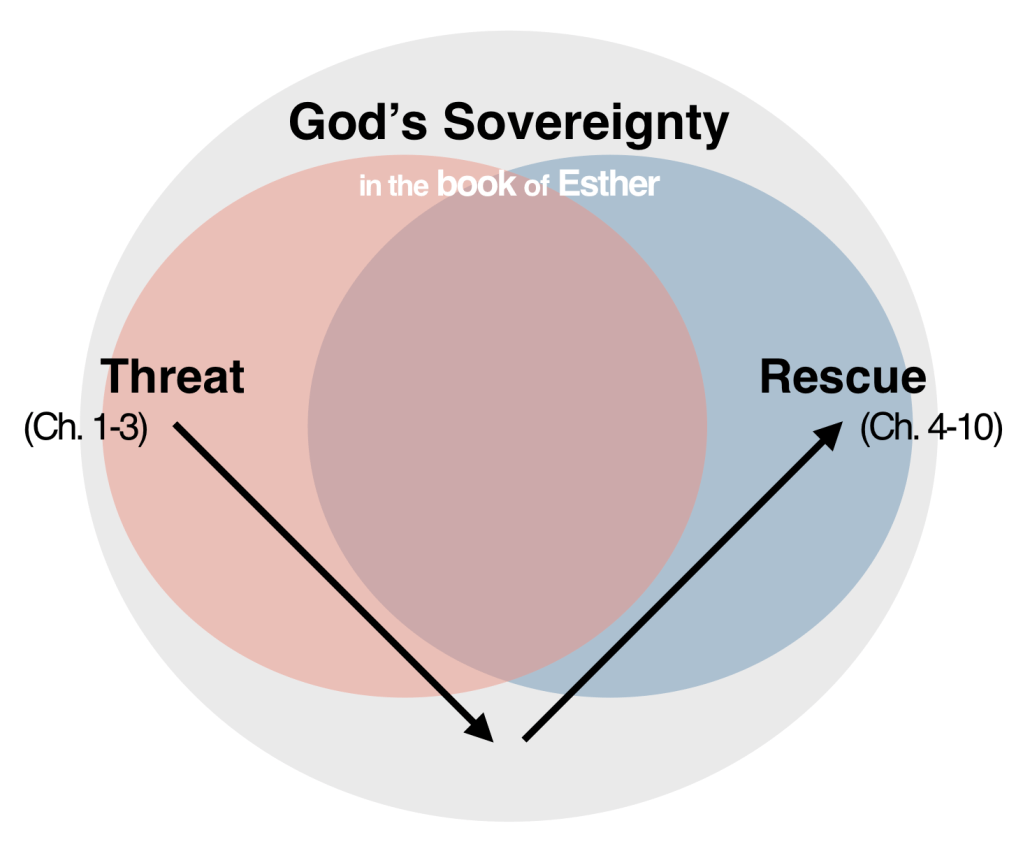

The book of Esther amazingly goes from fast to feast! God brings about all sorts of unlikely plot twists. Here’s a picture that shows us the plot of Esther:

God rescues in unexpected ways. He always has.

The story of Esther is intricately and intrinsically linked to the cosmic story of rescue. It is through the deliverance that happens in the book of Esther that the deliverance from Messiah Jesus can happen. If Haman’s pogrom would have succeeded then God’s promise would not have. God, however, keeps His promises. He did and will provide the rescue we all need. Jesus, the Messiah, the Promised One, was born of a woman, as a Jew, and a descendent of David. Jesus did strike a death blow to Satan, the serpent of old, when He died on the cross and rose victorious over death and sin, and He soon will send Satan to the fiery pit.

So, just as Esther brought rescue, Jesus brings eternal rescue. Esther and Jesus are similar in some ways but also very different. Unlike Esther, Jesus had “no beauty that we should desire Him. He was despised and rejected” (Is. 53.2-3). And unlike Esther who brought an amazing plot reversal akin to resurrection, Jesus actually brought resurrection, and final victory over Satan, sin, and death. So, Esther is good and we’re thankful for her but Jesus is clearly much better.

Esther brought reversal—from Jewish destruction to Jewish deliverance, from Mordecai being impaled high above the crowd to Haman being impaled high above the crowd, from a pogrom against the Jews to Jewish peace. But Jesus brings ultimate reversal. The dead shall rise. In the end, the last shall be first, and the first last. Those who weep will be comforted and rejoice.

The ultimate reversal is that victory comes through the cross. God works, and has always worked, in unexpected and glorious ways.

Lee Beach, the author of The Church in Exile, has said, God “is able to use marginalization and weakness for his missional purposes, and the church in the post-Christendom age needs to embrace this very Esther-like perspective at its core as it seeks to be the people of God in a foreign culture.”[17]

Conclusion

So friends, even as we face challenges in the changing world that we find ourselves in, we know that we serve the LORD who is all-powerful even when we can’t see Him. Even when we can’t see Him present, we can trust His promise. He will be with us. He will help us.

We know that He, in Messiah Jesus, has already provided the rescue we most need. So, we continue to live faithful lives in hope and trust.

Lastly, I have a challenge for you. One recent study by the Pinetops Foundation has said, “The next 30 years will represent the largest missions opportunity in the history of America. It is the largest and fastest numerical shift in religious affiliation in the history of this country… 35 million youth raised in families that call themselves Christians will say that they are not by 2050.”[18] What if God strategically raised you up for such a time as this? What if God want you to be on mission in exile?

To be honest, I don’t know what God is calling me to do about this. I don’t know what he’s calling you to do about this. But, perhaps, God has brought you to this point for such a time as this (cf. 4:14)? I want to take some time for us to pray and reflect on what God is leading us to do about the 35 million youth raised in Christian homes that are projected to leave the path of life for the path of destruction.

Esther took her life in her own hands, risked it all. What might God be calling you to?

Let’s take some time and ask our Father what He would have us do.

[1] Ryken, Ryken, Wilhoit, Ryken’s Bible Handbook, 207.

[2] Of course, it may not mean that the party was 180 consecutive days.

[3] Herodotus, Histories, 3.31.

[4] https://www.prri.org/wp-content/uploads/2016/09/PRRI-RNS-Unaffiliated-Report.pdf.

[5] Ibid.

[6] Haman is an Agagite which means he was a Canaanite which were longtime enemies of the Israelites. This comes into the plot of the story later on but this point is not made explicit.

[7] Charles F. Pfeiffer, Old Testament History, 489. That book, however, was published in 1973 so the figure would be higher today.

[8] Herodotus talks about such a book in Histories 8.85, 90.

[9] “Reversal seems the most important structural theme in Esther” (Dumbrell, Faith of Israel, 300 as quoted in Schreiner, The King in His Beauty, 224).

[10] Lee Beach, The Church in Exile, 79.

[11] John S. Dickerson,The Great Evangelical Recession, 126.

[12] Illustrated Summaries of Biblical Books by the Bible Project. “Even though God is never mentioned, Yahweh is King, and the Jews are his people. No plot to annihilate them will ever succeed, for Yahweh made a covenant with Israel and will fulfill his promises to them. The serpent and his offspring will not perish from the earth until the final victory is won, but they will not ultimately triumph. The kingdom will come in its fullness. The whole world will experience the blessing promised to Abraham” (Thomas R. Schreiner, The King in His Beauty, 225).

[13] Dever, The Message of the Old Testament, 462.

[14] Elliot Clark, Evangelism as Exiles, 42.

[15] See Dever, The Message of the Old Testament, 457ff.

[16] See Ibid.

[17] Beach, The Church in Exile, 79.

[18] “The Great Opportunity: The American Church in 2050,” 9. This is a study put out by the Pinetops Foundation.

Revelation: Triumph of the Lamb

Dennis E. Johnson’s book, Triumph of the Lamb: A Commentary on Revelation, has a lot of important and relevant things to teach us. Here are a few highlights from the introduction…

1. Revelation Is Given to Reveal.

2. Revelation Is a Book to Be Seen.

“One of the key themes of the book is that things are not what they seem. The church in Smyrna appears poor but is rich… What appear to the naked eye, on the plane of human history, to be weak, helpless, hunted, poor, defeated congregations of Jesus’ faithful servants prove to be the true overcomers who participate in the triumph of the Lion who conquered as a slain Lamb. What appear to be the invincible forces controlling history—the military-political-religious-economic complex that is Rome and its less lustrous successors—is a system sown with the seeds of its self-destruction” (p. 9).

3. Revelation Makes Sense Only in Light of the Old Testament.

“The ancient serpent whose murderous lie seduced the woman and plunged the world into floods of misery (Gen. 3:1) is seen again, waging war against the woman, her son, and her other children—but this time his doom is sure and his time is short (Rev. 12; 20)” (p, 13).

4. Numbers Count in Revelation.

For example, “The number seven symbolizes the Spirit’s fullness and completeness” (p. 15).

5. Revelation Is for a Church under Attack.

“Our interpretation of Revelation must be driven by the difference God intends it to make in the life of his people. If we could explain every phrase, identify every allusion to Old Testament Scripture or Greco-Roman society, trace every interconnection, and illumine every mystery in this book and yet were silenced by the intimidation of public opinion, terrorized by the prospect of suffering, enticed by affluent Western culture’s promise of ‘security, comfort, and pleasure,’ then we would not have begun to understand the Book of Revelation as God wants us to… Always, in every age and place, the church is under attack. Our only safety lies in seeing the ugly hostility of the enemy clearly and clinging fast to our Champion and King, Jesus” (19).

6. Revelation Concerns “What Must Soon Take Place.”

7. The Victory Belongs to God and to His Christ.

“Revelation is pervaded with worship songs and scenes because its pervasive theme—despite its gruesome portrait of evil’s powers—is the triumph of God through the Lamb. We read this book to hear the King’s call to courage and to fall down in adoring worship before him” (p. 23).

C.S. Lewis on Scientism in Out of the Silent Planet

Have you ever heard of C.S. Lewis’ book series, The Chronicles of Narnia? It’s good. But, Lewis’ Ransom Trilogy is even better. And one of the reasons for that is because he confronts scientism.

Scientism

Scientism exalts the natural sciences as the only fruitful means of investigation. In the words of Wikipedia: “Scientism is the promotion of science as the best or only objective means by which society should determine normative and epistemological values.” In short, scientism is the view that says science, and science alone, tells us what is right and true.

Science, of course, is different. It is the study of the natural world through systematic study (observation, measurement, testing, and adjustment of hypotheses). Scientism goes beyond science and beyond the observation of the physical world into philosophy and ethics.

How can observations about the natural world tell us how to think and live? How can science tell us how to best do science? What can be said about the problems of scientism? C.S. Lewis gives us a few things to think about, and in a very enjoyable way.

Out of the Silent Planet on Scientism

Weston, one of the main characters in C.S. Lewis’ book, Out of the Silent Planet, holds to a form of scientism and belittles other ways of acquiring knowledge. Unscientific people, Weston says, “repeat words that don’t mean anything”[1] and so Weston refers to philology as “unscientific tomfoolery.” The “classics and history” are “trash education.”[2] He also says that Ransom’s “philosophy of life” is “insufferably narrow.”[3]

When science is the sole means of knowledge then we are left without theology, philosophy, and ethics. We are left to decipher ought from is. And it can’t be done. Or not in a way that prevents crimes against humanity. “Intrinsically, an injury, an oppression, and exploitation, an annihilation,” Nietzsche says, cannot be wrong “inasmuch as life is essentially (that is, in its cardinal functions) something which functions by injuring, oppressing, exploiting, and annihilating, and is absolutely inconceivable without such a character.”[4]

Weston concurs. He is ready and willing to wipe out a whole planet of beings. He says, “Your tribal life with its stone-age weapons and bee-hive huts, its primitive coracles and elementary social structure, has nothing to compare with our civilization—with our science, medicine and law, our armies, our architecture, our commerce, and our transport system… Our right to supersede you is the right of the higher over the lower.”[5]

It is about life. Looking at life, looking at survival alone, leads us to think that alone is the goal. My life versus your life, Weston’s life versus the Malacandrian lives. That’s what we get when we derive ought from is. “Life is greater than any system of morality; her claims are absolute.”[6] And so, if it would be necessary, Weston would “kill everyone” on Malacandra if he needed to and on other worlds too.[7] Again, Weston finds agreement in Nietzsche: “‘Exploitation’ does not belong to a depraved, or imperfect and primitive society: it belongs to the nature of the living being as a primary organic function.”[8]

Conclusion

Is Weston’s view correct? No. And we know it. That is the point C.S. Lewis makes. He offers a narrative critique of scientism in Out of the Silent Planet as well as through the whole Ransom Trilogy. He shows the havoc that scientism sheared of theology, philosophy, and ethics can unleash.

The answer is not to discard science, however. That is not what Lewis proposes either, though that is what some protest. The answer is to disregard scientism. Science is great and a blessing from God, but science on its own is not enough as our guide. We cannot, for example, derive ought from is. We cannot look at the natural world around us, at what is, and find out what we should do, how we ought to live.

Notes

____

[1] C.S. Lewis, Out of the Silent Planet (New York: Scribner Paperback Fiction, 1996), 25.

[2] Lewis, Out of the Silent Planet 27.

[3] Ibid.

[4] Friedrich Nietzsche, The Genealogy of Morals.

[5] Lewis, Out of the Silent Planet, 135.

[6] Ibid., 136.

[7] Ibid., 137.

[8] Friedrich Nietzsche, Beyond God and Evil, par. 259.

20 of the best books I read in 2019

Here are twenty of my favorite books that I read in 2019. I think I only read three fiction books this year. I need to fix that. I plan to read quite a bit more fiction next year. Anyhow, here’s some of my favorites… (in no particular order)

- Why Suffering?: Finding Meaning and Comfort When Life Doesn’t Make Sense

by Ravi Zacharias - Safely Home by Randy Alcorn

- Apologetics at the Cross: An Introduction to Christian Witness by Josh Chatraw and Mark D. Allen

- Them: Why We Hate Each Other–and How To Heal by Ben Sasse

- How Long O Lord?: Reflections on Suffering and Evil by D.A. Carson

- Titan: The Life of John D. Rockefeller, Sr. by Ron Chernow

- Alienated American: Why Some Places Thrive While Others Collapse

by Timothy P. Carney - Holy Sexuality and the Gospel: Sex, Desire, and Relationships Shaped by God’s Grand Story by Christopher Yuan

- Remember Death: The Surprising Path to Living Hope by Matthew McCullough

- The Autobiography of Martin Luther King Jr by Clayborne Carson

- Today Matters: 12 Daily Practices to Guarantee Tomorrow’s Success by John C. Maxwell

- Elon Musk: Tesla, SpaceX, and the Quest for a Fantastic Future by Ashlee Vance

- Walking with God through Pain and Suffering by Timothy Keller

- Preaching as Reminding: Stirring Memory in an Age of Forgetfulness by Jeffrey D. Arthurs

- An Unhurried Leader: The Lasting Fruit of Daily Influence by Alan Fadling

- Everyday Church: Gospel Communities on Mission by Tim Chester and Steve Timmis

- Susie: The Life and Legacy of Susannah Spurgeon, wife of Charles H. Spurgeon by Ray Rhodes Jr.

- To the Golden Shore: The Life of Adoniram Judson by Courtney Anderson

- Endurance: Shackleton’s Incredible Voyage by Alfred Lansing

- Deep Work: Rules for Focused Success in a Distracted World by Cal Newport

Out of all the books I read last year, Remember Death by Matthew McCullough, is the one I would suggest you read over all the rest.

Read it.

A Pre-Civil War “Conversation” on Slavery

Introduction

In writing this I read and analyzed two pre-Civil War articles.[1] The first article we will look at argues in favor of the continuation of slavery. The second article is written in response to the first and argues for immediate abolition. After looking at both articles we will look at the differences between the two articles.

My thesis is that some, like Buck, advocated for the continuance of slavery mainly based upon the belief that slavery was permitted because it was similar to the slavery permitted in the Old Testament. Others, however, like Pendleton, argued against slavery because they believed it was inherently dissimilar to Old Testament slavery.

In Favor of the Continuation of Slavery

Since “the subject is one of great moment in its moral, social and political bearings”[2] Buck decided to write on the subject. “So that… [people] may be prepared to act conscientiously and intelligently, and have no occasion to repent of their action when it is too late to undo it.”[3] So, it was “under… these considerations [that Buck] consented to prepare a series of articles.”[4]

Buck says, “God approves of that system of things which, under the circumstances, is best calculated to promote the holiness and happiness of men; and that what God approves is morally right.”[5] Buck then talks about the “nature and design of Human Governments.”[6] He says, “In searching the divine record, therefore, we shall find that form of government which, under the circumstances, was best calculated to promote the moral and social happiness of the people, was sanctioned and approved by God.”[7]

The first form of government was the patriarchal, which Buck gives a brief analysis of. Next he lays out what he sees as being established through his belief that God has a good purpose for human governments. First, he says, “God has beneficent and gracious designs to be accomplished in behalf of the human family.”[8] Second, God is happy to use human and governmental instruments. Third, it is in accord with God’s infinite wisdom “to promote his beneficent and gracious designs in behalf of our lapsed and degenerate world.”[9] Fourth, a very powerful and enlightened leader is best suited to bring about the good that God intends for humanity.

Elliot Clark, Evangelism as Exiles

I really appreciated Elliot Clark’s book Evangelism as Exiles. Here are some of the things that stood out to me:

“Picture an evangelist. For many of us, our minds immediately scroll to the image of someone like Billy Graham—a man, maybe dressed in a suit and tie, speaking to a large audience and leading many to Christ. As such, we tend to envision evangelism as an activity—more commonly a large event—that requires some measure of power and influence. In communicating the gospel, one must have a voice, a platform, and ideally a willing audience. It’s also why, to this day, we think the most effective spokespeople for Christianity are celebrities, high-profile athletes, or other people of significance. If they speak for Jesus, the masses will listen. But this isn’t how it has always been. Not throughout history and certainly not in much of the world today” (Clark, Evangelism as Exiles).

Elliot Clark gives six essential qualities of a Christian exile on mission:

“With the help of God’s Spirit, such believers will be simultaneously (1) hope-filled yet (2) fearful. They will be (3) humble and respectful, yet speak the gospel with (4) authority. They will live (5) a holy life, separate from the world, yet be incredibly (6) welcoming and loving in it. While these three pairs of characteristics appear at first glance to be contradictory, they are in fact complementary and necessary for our evangelism as exiles” (Clark, Evangelism as Exiles).

“From the perspective of 1 Peter, the antidote to a silencing shame is the hope of glory, the hope that earthly isolation and humiliation are only temporary. God, who made the world and everything in it, will one day include us in his kingdom and exalt us with the King, giving us both honor and also a home. We desperately need this future hope if we want the courage to do evangelism as exiles” (Clark, Evangelism as Exiles).

Here is a long string of quotes I found instructive:

“over the last decades, in our efforts at evangelism and church growth in the West, the characteristic most glaringly absent has been this: the fear of God… “Knowing the fear of the Lord, ” [Paul] explained, “we persuade others” (2 Cor. 5:11)… The consistent testimony of the New Testament is that if we have the appropriate fear for them and of God, we’ll preach the gospel. We’ll speak out and not be ashamed… our problem in evangelism is fearing others too much” (Clark, Evangelism as Exiles).

“In a world teeming with reasons to be terrified, the only rightful recipient of our fear, according to Peter, is God… Fear of him, along with a fear of coming judgment, is a compelling motivation to open our mouths with the gospel. But we do not open our mouths with hate-filled bigotry, with arrogant condescension, or with brimstone on our breath. According to Peter, we fear God and honor everyone else” (Clark, Evangelism as Exiles).

“According to Peter, we’re to honor everyone. Take a moment and turn that thought over in your mind. You’re called to show honor to every single person. Not just the people who deserve it. Not just those who earn our respect. Not just the ones who treat us agreeably. Not just the politicians we vote for or the immigrants who are legal. Not just the customers who pay their bills or the employees who do their work. Not just the neighborly neighbors. Not just kind pagans or honest Muslims. Not just the helpful wife or the good father” (Clark, Evangelism as Exiles).

Some of the most significant theological books I have read…

Here is a list (in no particular order) of some of the most significant theological books I have read.*

- God’s Glory in Salvation Through Judgment By James Hamilton

- From Eden to the New Jerusalem and The Servant King by T. D. Alexander

- The Imitation of Christ by Thomas A Kempis

- The Cost of Discipleship by Dietrich Bonhoeffer

- The Doctrine of God and The Doctrine of the Word of God by John Frame

- Knowing God by J. I. Packer

- Money, Possessions, and Eternity by Randy Alcorn

- Systematic Theology by Wayne Grudem

- Desiring God, Don’t Waste Your Life, God is the Gospel, Future Grace and Let the Nations be Glad by John Piper

- The Knowledge of the Holy by A.W. Tozer

- New Testament Theology and The King in His Beauty by Thomas R. Schreiner

- Foundations of Soul Care by Eric Johnson

- The Cross of Christ by John Stott

- Mere Christianity by C.S. Lewis

- Death by Love by Mark Drisscol

- The Universe Next Door by James Sire

- Dangerous Calling by Paul Tripp

- The Resurrection of Jesus by Michael Licona

- Desiring the Kingdom by James K. A. Smith

- Radical by David Platt

- Center Church by Timothy Keller

___________________________

*This is a personal list of books that helped me in a particular way at a particular time. This is not a list on the best and most significant theological books; that list would look different.

30 Insights to remember from Preaching as Reminding

I really appreciated Jeffrey D. Arthurs’s book, Preaching as Reminding. Here are thirty things I especially want to remember…

“The Scriptures themselves are the invitation to remember: Remember Abraham, Isaac, and Jacob; remember the Exodus; make a pile of stones; remember the Sabbath. Come again to the table, break the bread, drink the cup. Remember” (Jeffrey D. Arthurs, Preaching as Reminding, p. ix).

Preachers “remind the faithful of what they already know when knowledge has faded and conviction cooled. We fan the flames. That’s what we see when we look at the work of Moses, the prophets, and the apostles” (p. 3). “Preachers are remembrancers” (p. ix). We see this for example through what Peter says in 2 Peter 1:12-13 (“…to stir you up by way of reminder…”). And so, “Ministers must learn to stir memory, not simply repeat threadbare platitudes” (p. 5).

“It matters that we preach. It matters that we call people to remember their God and their deepest values and their truest selves and the story that has maybe shaped their lives and for sure has shaped their world. It matters that we preach with all the fidelity and urgency and learning and purity and creativity that God allows us to muster” (p. ix-x).

“If we have no memory we are adrift, because memory is the mooring to which we are tied. Memory of the past interprets the present and charts a course for the future” (p. 1). “Without memory, we are lost souls. That is why the Bible is replete with statements, stories, sermons, and ceremonies designed to stir memory. Even nature—the rainbow after the flood—serves as a reminder of God’s faithfulness (Gen 9:13-17)” (p. 3).